How a dull and dangerous building hinders our Midwest research university and its students

Dunbar Hall is an unsafe eyesore. The university doesn’t want to showcase it, the state hasn’t been able to pay for it for the last two decades, no private investors want to invest because of the lack of chemistry companies in the area and no one in their right minds would want to work or study in it.

Simply put, Dunbar Hall is a burden to the chemistry department here at North Dakota State for both students and staff.

And this isn’t a uniquely NDSU problem; there are buildings like Dunbar Hall all across this country.

The problem that NDSU and many universities face is ugly, cheap buildings that are doomed for a wrecking ball rather than reverence because of the time period they were built in. That is a big problem for the future of higher education, which needs to find a way to replace these buildings to remain competitive, especially Midwestern research universities that don’t have billion-

The question we should be asking now is what value do we put on the brick and mortar campus experience? How does that impact local economies and what is the future for NDSU and universities like it?

Built in 1963, Dunbar Hall represents a generation of buildings that still have a healthy population on NDSU’s campus.

Deferred maintenance

I sat down with Michael Ellingson, the director of Facilities Maintenance here at NDSU. For casual observers, it is easy to walk into a building and complain, but Ellingson has to balance those complaints with a lot of politics and, more importantly, the budget he is allocated from the state.

Talking with him it became apparent that Dunbar isn’t an easy fix. Dunbar is a problem that is decades old.

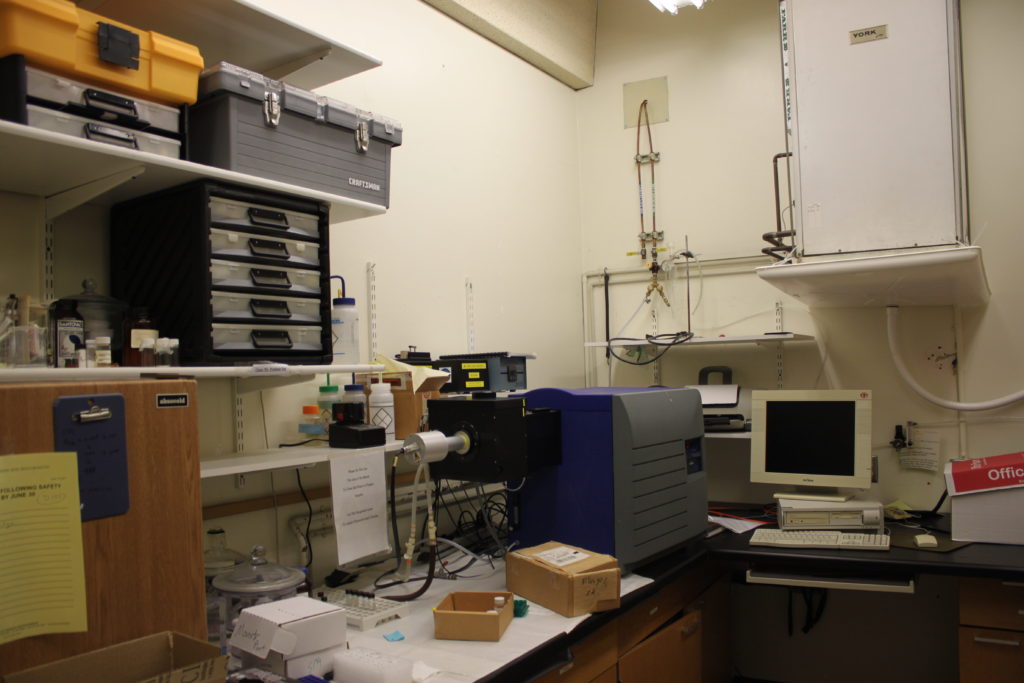

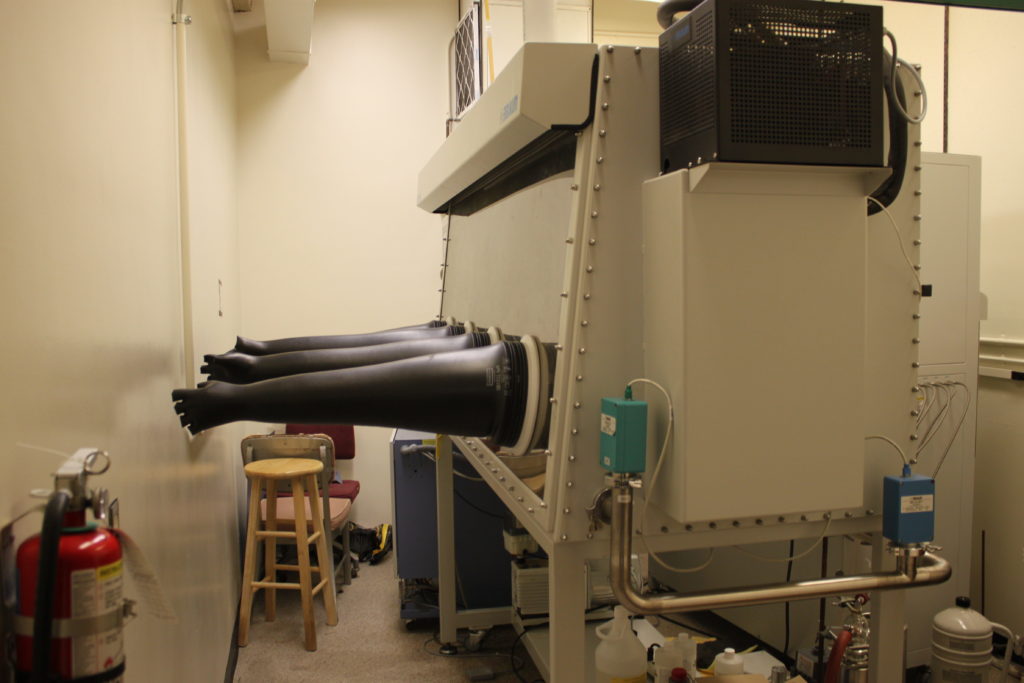

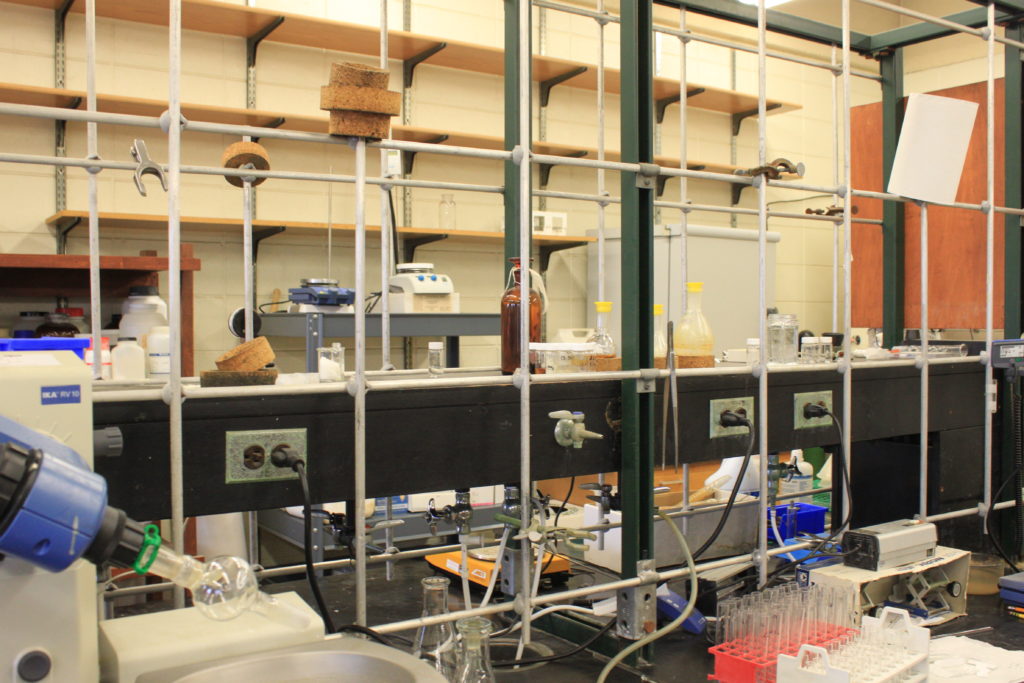

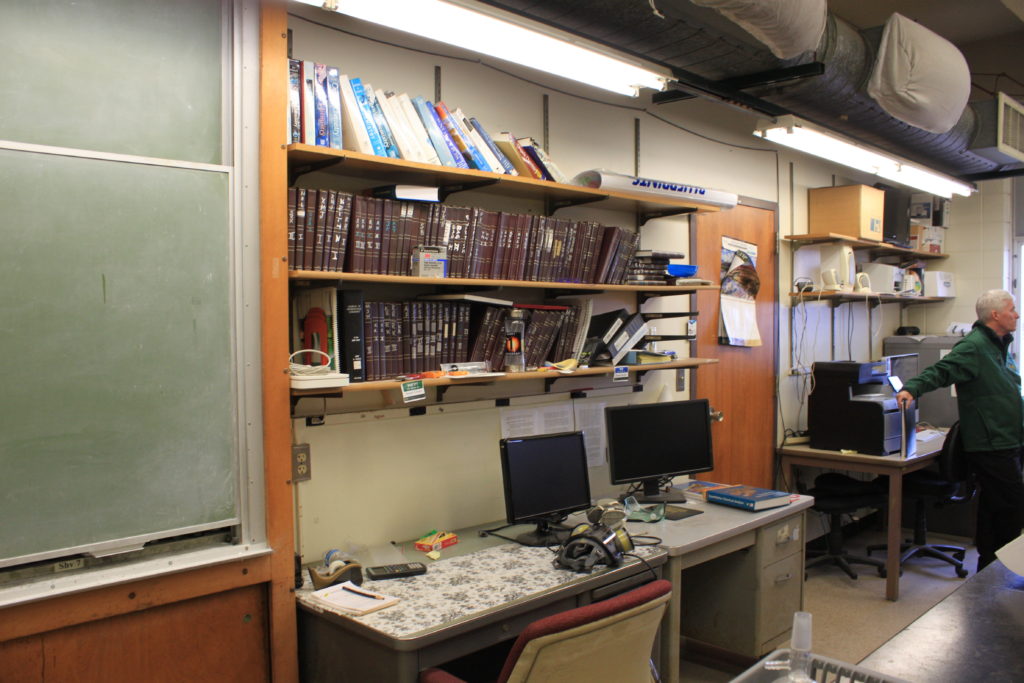

“There are a lot of things in Dunbar that are at their finite life,” Ellingson said. He told me that a building, especially Dunbar which is tasked with chemical storage and ventilation of chemicals, is particularly hard on the HVAC systems. In short, the system needs replacing.

“For 20 years we’ve had metallic dust particles blowing out of the ventilation, covering our labs,”

Gregory Cook professor and chair of the chemistry department

“For 20 years we’ve had metallic dust particles blowing out of the ventilation, covering our labs,” said Gregory Cook, professor and chair of the chemistry department. He told me about how he has to deal with this ventilation system by sweeping up that dust multiple times a week.

Walking through Dunbar Hall with Cook, it became apparent that Dunbar Hall is a major problem. In 2014, a Forum letter to the editor titled, “Funding for Dunbar Hall a no-brainer,” argued that “a case can be made that conditions in Dunbar pose health and fire dangers.”

In 2017, almost exactly three years after that letter, the chemistry department lost an entire lab to fire.

“It’s literally held together by duct tape and bayling wire.”

Dean Bresciani NDSU President

Cook told me they lost an eighth of their space for research in Dunbar for their department, and today, that lab remains vacant and unused.

Dunbar in particular has had issues due to the changing of chemistry over time. To put it simply, Dunbar wasn’t built for chemistry today. In the words of NDSU President Dean Bresciani, “It’s

Fixing these problems isn’t so easy though. Updating the ventilation system would require fixing everything that isn’t up to code. In Dunbar, it seems like everything is not up to code.

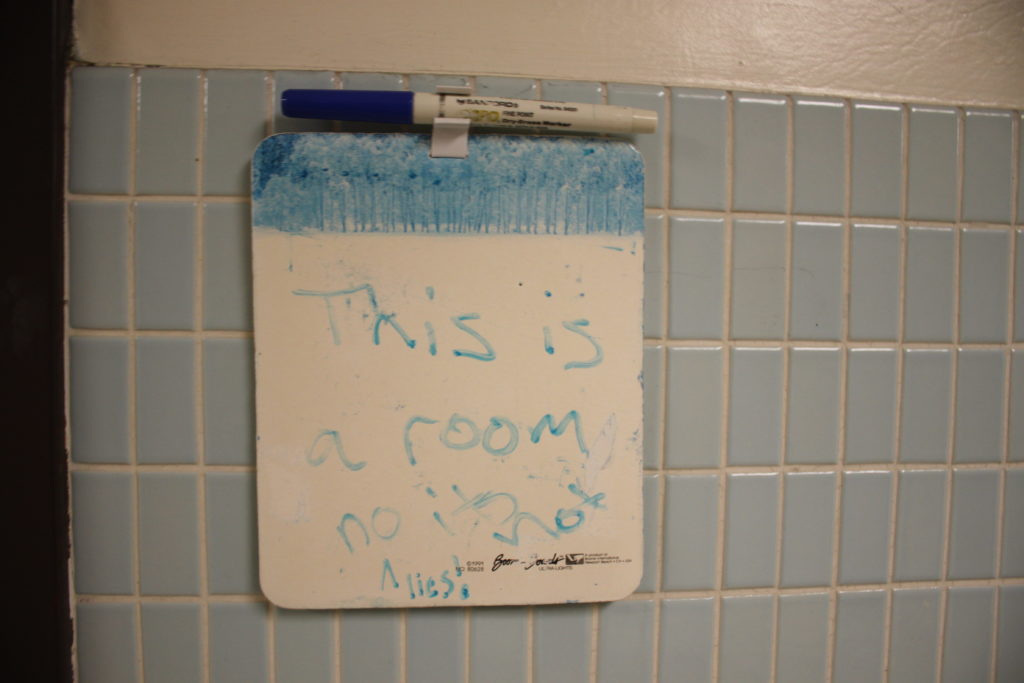

Ellingson put it this way when talking about the bathrooms, “I can’t just fix the plumbing.” Updating a bathroom’s plumbing requires bringing the rest of the bathroom up to code, which is set globally and sometimes nationally.

Ensuring the plumbing works would require Ellingson to add fixtures, add a fire suppressant system and add bathrooms on every floor that code calls

“We don’t have the capital … You’re at the mercy of the state,” Ellingson said. His words are right. Right now, the state is deciding whether they want to fund a bond to invest in both Dunbar Hall and Harris Hall.

House Majority Leader Chet Pollert, R-Carrington, suggested to cut the amount of money invested by the state by nearly 20% for Dunbar Hall, going from the approved $51.2 million to $40 million. He also proposed axing the $54 million investment for Harris Hall.

That is Ellingson’s job, which is difficult to say the least when he has to worry about replacing a building that everyone who has experienced it agrees needs serious attention.

Ellingson told me in a walkthrough that he gets roughly 50 calls a day for maintenance. “I can’t even count how many times I’ve been in Dunbar,” he said.

He also has to make sure buildings keep water out and are habitable, no matter what happens at the state legislature.

So, Dunbar needs replacing. It may get replaced, and less might be offered through the state as far as funding. Why do we have this issue though? Why is Dunbar falling apart where buildings like Old Main and South Engineering are still standing the same as ever?

Old Main, built in 1891, display a very different approach to building construction compared to Dunbar.

“We will never have another building built like Old Main,”

Mike Tonder State Board of Higher Education director of facilities planning

We will never have another Old Main

Old Main, the building that currently holds the president’s office, is a year younger than the state of North Dakota; construction on the building started in 1891.

In comparison, Dunbar’s construction started in 1963. Which begs the question, why is Dunbar being torn down while Old Main remains standing and will for the foreseeable future?

“We will never have another building built like Old Main,” said Mike Tonder, the State Board of Higher Education director of facilities planning. When comparing an old building like Old Main to a newer building like Dunbar, it is important to understand that at the turn of the 20th century, roughly 80% of a building’s budget went to structural components, which have longer lifespans than mechanical systems.

Now, however, mechanical systems that have a much, much shorter lifespan make up roughly 50% of a budget for a new building.

During Dunbar’s construction there was also something else happening, a boom in university population.

“The majority of our buildings are in the 50-75 (years) old range … the number of projects outstripped the resources, so you found people building the most utilitarian, minimalist building,” Bresciani said, which is why Dunbar Hall will be torn down instead of being maintained.

This means the lifespan of buildings is shorter for newer buildings, but what about our newest buildings?

“Now’s the time to address the worst building on a college campus in North Dakota.”

Mason Rademacher executive commissioner of Student Affairs for student government and student body president-elect.

“There has to be the mindset from students as well as administration that we want to champion some of our historical buildings on campus,” said Mason Rademacher, the executive commissioner of Student Affairs for student government and student body president-elect.

Rademacher has had Dunbar on his mind for some time, as he works in advocating for Dunbar Hall at the state legislature.

During the student government president-vice president debate, Rademacher said, “Now’s the time to address the worst building on a college campus in North Dakota.”

That is saying a lot. Dunbar is bad, but is it the worst?

“It stinks,” Cook said. He explained many issues, including air quality, smells he can’t find the source of and even having to move staff out of Dunbar over health concerns.

“It is inhibiting both research and graduate education,”

Gregory Cook professor and chair of the chemistry department

“The only way to get out is to jump out of third-story windows,” Cook said. He also said there are many concerns about the safety of some research areas, and in short, “We hope there’s never a fire.”

This concern over safety doesn’t stop Cook from worrying about the future of higher education’s campuses though, saying that he hates to see buildings torn down. In Dunbar’s case though, there doesn’t seem to be an option.

“It is inhibiting both research and graduate education,” Cook said. He told me that although there have been requests to either build on to or replace Dunbar for over 20 years and over his entire career as chair of the department, there just hasn’t been a solution yet.

The future of brick and mortar

I asked everyone I sat down with the following question, what will NDSU look like in 100 years? The answers I got varied, but many followed the same path.

“I don’t know what higher education will look like in 100 years,” Rademacher said. He told me that he sees two possibilities: one where higher education is more online, and another where brick and mortar is still valued.

“I think that in terms of soft skill development, that the brick and mortar ‘butts in seats’ model is very important to student development,” he said, pointing to his experience in student government and the connection to history that students get when they interact with the infrastructure on campus.

“For every $1 spent on higher education by the state, NDSU puts $7 back in the state economy,”

Dean Bresciani NDSU President

“That is what companies are looking for,” President Bresciani said. He also noted that he learned more from interacting on campus and from talking to his peers over materials than just reading a book.

“I have a hunch that as we have evolved in the last 1000 years, we will evolve in the next 100,” Tonder said, telling me that he sees a future where students may be studying in inflatable buildings with virtual reality headsets on.

When asked if students appreciate the

To me, the infrastructure a university can offer is fundamentally one of the most valuable things to a student and the region it is in. Being reminded that thousands have walked in your paths, that much greater struggles have occurred beforehand is important for human development.

“For every $1 spent on higher education by the state, NDSU puts $7 back in the state economy,” President Bresciani said, also noting that NDSU was at once a throwaway idea. The state offered up a prison or an agricultural college to either Bismarck or Fargo. The rest is history.

As that plan has progressed, we can see Fargo as one of the faster growing cities in the country, with NDSU being in the top 100 for research universities.

I pulled Cook aside and asked him about what his college will look like in 10 years, or when he is planning on potentially retiring.

“I think we can better serve the state and region if we have the proper facilities to do research in.” Cook said that after the Dunbar fire, their graduate numbers took a hit, falling from the 60s down into the 50s. At the moment, the potential is there for the chemistry department and potentially attracting new industry, but it needs a catalyst first, and that is funding.

To the state, the solution to generating more revenue and investing in North Dakota seems pretty simple — fund Dunbar Hall.