Life and land in North Dakota get the spotlight in Jack Dura’s NoDak Moment photo series. From landscape scenery to natural curiosities to culture across the state, there are countless sites of interest in North Dakota, from the legendary to the little-known. Now that’s a NoDak Moment.

________________________________________________________________________________________

End of the Line

Temperatures hit the 100s for southwestern North Dakota in early August 1892 when surveyor Charles H. Bates and a work crew installed the last monument out of 720 along the North Dakota-South Dakota border.

After tracking down the tripoint of the Dakotas and Montana, Bates and his men planted the 7-foot, 800-pound, quartzite Dakota marker labeled as the terminal monument. The marker concluded what is arguably one of the most remarkable surveys and delineations of a border in the world, with one marker installed every half-mile for 360 miles. Few other boundaries are marked so conspicuously at such intervals for such a length.

The quartzite border, as literature calls it, has withstood nearly 125 years of the Dakotas’ development, from agriculture to road construction. Bates’ crew worked west in fall 1891 from the Bois de Sioux River near the tripoint of Minnesota and the Dakotas, stopping work after two months due to winter weather.

They began again in June 1892, finishing two months later along a boundary that brought such troubles as rough topography, insects, snowstorms, heat, wind and little water. Despite these climate troubles, the Dakotas’ border, surveyed along the seventh standard parallel, is highly accurate as contemporary surveyors say. Bates’ measurements along the boundary were guided by state-of-the-art equipment and frequent check-ins with the star Polaris.

Many of the monuments still stand, practically unchanged after over a century due to quartzite’s properties. However, hundreds have fallen to farming, road construction and thieves. The Dakota markers are now under the umbrella of the Bureau of Land Management. Owning or removing a marker is in violation of federal laws.

Despite this, North Dakota State displays a half-mile monument from south of Scranton, N.D., in the university’s Grandmother Earth’s Gifts of Life Garden. NDSU took out a 99-year lease in 2007 from the BLM for the monument, broken at its base and weighing about 400 pounds. A former NDSU football player found and brought the monument to Fargo where he displayed it on his lawn before Fargo Police stepped in.

NDSU’s regular matchup against South Dakota State pays tribute to the border in title, with a miniature granite replica of the monuments as a trophy for the Dakota Marker game.

The initial monument, south of Fairmount, N.D., and the terminal monument, south of Marmarth, N.D., still stand and bookend the Dakotas’ boundary of slightly more than 360 miles. Travelers can drive right up the initial monument, while the terminal monument requires a walk of over three miles from a rarely traveled gravel road. Both are special in relation to boundary, as they mark where the Dakotas begin and end and touch.

Despite their removal, vandalism and remoteness, the Dakota markers were editorialized at the time of their installation to “remain undisturbed until the time when we are called from our graves to attend of the proceedings of the Day of Judgement.”

Editor’s note: This feature is the last in a photo series chronicling legendary and little-known spots in North Dakota.

___________________________________________________________________________

Building Bridges

New Town, N.D., has its beginnings in a sad end.

The city is a main community of the Fort Berthold Reservation and was created out of the certainty that the rising waters of Lake Sakakawea, dammed by the Garrison Dam to the south, would flood the towns of the reservation. That certainty came to pass, and New Town was platted in 1950, named such because no proposal or vote was held to name the “new town.”

Over 900 people from the flooding towns of Sanish and Van Hook, N.D., had to relocate to higher ground. Many people flocked to the New Town site, near Crow Flies High Butte, a prominent landmark near the Missouri River. New Town’s first business was a bar, with a lumber company to follow. While buildings were relocated and communities uprooted, construction began on a new bridge to span the length of the rising river. This was the Four Bears Bridge and was the second of three bridges with that name.

The first Four Bears Bridge was built in 1934 near Elbowoods, N.D., a town that’s also underwater now. When the rising river water made a need for a new bridge, the center span of the first Four Bears Bridge was removed and sent 40 miles upstream to be a part of the new, second Four Bears Bridge. Building began on that structure and was completed in 1955. The bridge served travelers on North Dakota Highway 23 for 50 years.

The second Four Bears Bridge was demolished and replaced with a third Four Bears Bridge finished in 2005, costing $55.5 million. One man died during a construction accident at the bridge in 2004. At 4,483 feet long, the bridge near New Town is North Dakota’s longest bridge.

Perhaps the best view of the bridge and the massive countryside is from the top of Crow Flies High Butte, named for a Hidatsa chief. The large hill offers a scenic overlook of Lake Sakakawea, the Four Bears Bridge and the remains of Old Sanish, N.D. The concrete foundation of the town’s elevators can still be seen poking through the water.

Several explorers are said to have visited the butte on their journeys, including Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in 1805 and 1806 and possibly Pierre Gaultier de Verendrye, the first European man recorded to have visited modern North Dakota, in 1738.

___________________________________________________________________________

(Two Thirds of) A Mile High

North Dakota’s highest point is no mountain and the path to get there is more of a hike than a climb.

White Butte south of Amidon, N.D., sits at 3,506 feet above sea level, not even a mile high. Montana’s highest point, just 325 miles west as the crow flies, sits over 9,000 feet above White Butte. A staggering climb, no doubt.

Situated in lonely, rolling Slope County, White Butte is perhaps the biggest tourist attraction to North Dakota’s least populated county (760 people). While the butte is on private land, the landowners are courteous enough to let strangers wander onto their property to walk the dusty, chalky trail to the top of White Butte. Actor Michael J. Fox even walked the trail last summer as part of a fundraising event for Parkinson’s disease.

White Butte is a windy place where rattlesnakes are known to hang out and cacti flourish. The view at the top of North Dakota is marvelous, looking out over the surrounding countryside and its vast, undulating openness.

For years, White Butte wasn’t even considered the state’s highest point. The honor was thought to belong to nearby Black Butte, a landmark just 40 feet shorter than White Butte. Still, some North Dakotans balk at White Butte and claim another butte in the state is the highest, allegedly four or so inches taller.

But the U.S. Geological Survey has recognized White Butte as North Dakota’s highpoint since 1962, and a pike at the peak references this federal honor.

Other high points in North Dakota include the Killdeer Mountains, Bullion Butte and the Chalky Buttes, the latter of which includes White Butte.

Of the 50 states’ high points, White Butte is the 30th highest summit but one of few found on private land. Its hiking trail is considered one of the most accessible in the state by several guidebooks to North Dakota hiking.

___________________________________________________________________________

The Road of Anticipation

One of North Dakota’s most popular and promoted tourist destination’s is a 32-mile stretch of highway decorated with scrap metal sculptures.

The Enchanted Highway is uniquely folksy. Gary Greff, the artist from Regent, N.D., designed, welded and constructed the pieces of roadside art across the last quarter-century. The Enchanted Highway pieces range from deer silhouettes to scrap metal game fish to a tin family.

They each took years to create but stand and sway in the northern winds as travelers journey north and south along the unnumbered, two-lane highway off Exit 72 on Interstate 94.

The seven sculpture works stand at various distances along the road to Regent, unevenly paced. Some have been on the roadside for nearly two decades and rust and wind have worked their effects on the larger-than-life artworks.

Several sprigs of metal grain stalks stand bent or broken at “Grasshoppers in the Field.” A dorsal fin fell of a large rainbow trout at “Fisherman’s Dream.” Pigeons have made their homes in several of the sculptures, and the wind constantly sways the structures.

Despite some needed maintenance, the Enchanted Highway marches on. Greff intends to build an eighth installment along the highway, “Spider Webs,” his first work in nearly 10 years. Greff’s project came about as a way to save his hometown from declining. Today the Enchanted Highway has helped build a hotel, ice cream shop, tourist shop and other draws in Regent.

Not to be outdone, Lefor, N.D., 18 miles north Regent, laid out the crumbling vault of its bank that went under in 1934, just off the Enchanted Highway. Travelers can step inside the vault and marvel at the interior and battered door.

North Dakota has little to no fame as a visual art haven, but its folk art ranges greatly, the Enchanted Highway perhaps the largest example in the state. Wrought-iron crosses, a German-Russian folk practice in the state since the 1870s, mark the graves of thousands of pioneers and prairie residents from Golden Valley to Mandan to Zeeland.

Mailbox designs and town welcome signs are other examples of metal folk art in North Dakota, found in towns like Woodworth and various farm homes along Highway 36. Murals are another visual art practiced in the state, usually focused on rural themes like agriculture and wildlife.

Towns like Rutland and Tioga have sprawling murals in their downtowns, and Jud bills itself as the Village of Murals with large painted works spanning many buildings’ sides.

________________________________________________________________________________________

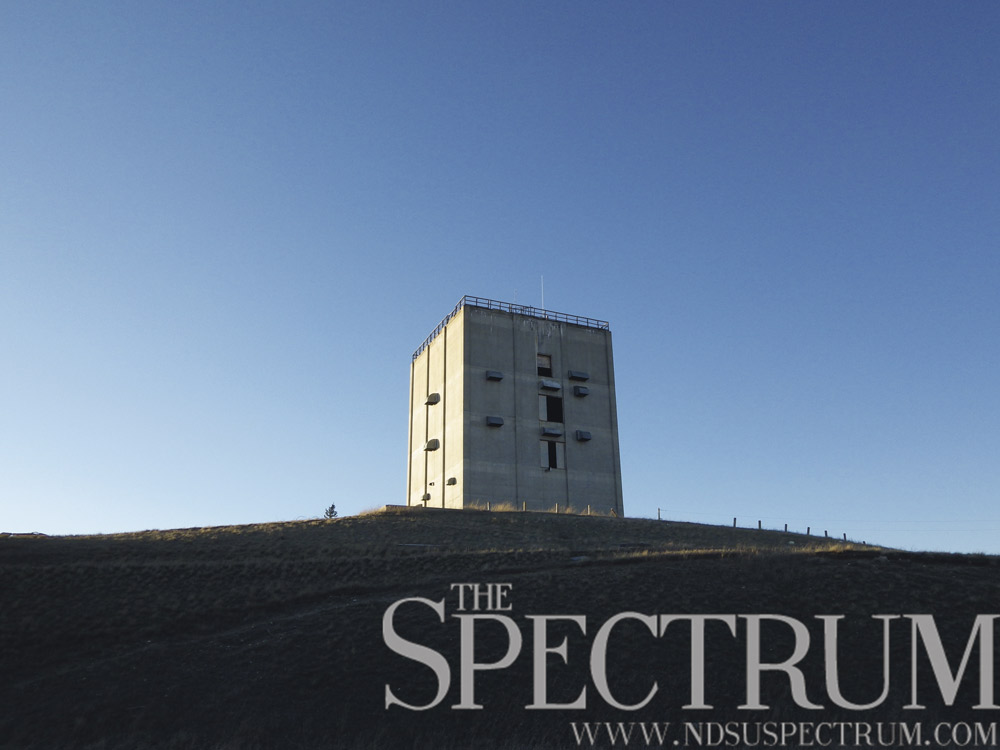

Cold War in Fortuna’s Corner

The Cold War had a big presence in North Dakota for a number of years with radar and defense facilities scattered from Finley to Minot to Nekoma. The U.S. Air Force operated these bases, including the sprawling Fortuna Air Force Station located on North Dakota Highway 5, west of Fortuna, N.D.

The facility, opened in 1952, was a ground control intercept station built to guide interceptor aircraft toward unidentified objects in airspace. Sitting on a highpoint on the North Dakota prairie, the base’s radar dishes were occasionally toppled by wind. As the Cold War progressed and technology evolved, so did the base’s mission. By 1979, the base was partly deactivated before compete deactivation in 1984. Since then, the base has been abandoned.

The large facility included radar dishes and domes, officer housing including 45 houses and some dormitories, a dining hall, nightclubs, a gymnasium, a motor pool and a bowling alley, among other structures. All sat idle for three decades before last summer when Divide County government began demolition on the base. At a rate of one building per day, the demo crew worked toward restoring the base to the prairie in a reclamation effort. Two buildings will remain standing: the five-story, cement radar tower and one smaller building.

Currently the radar tower is home to communications equipment for wireless internet and mobile phone coverage for rural customers. These updates in technology come in contrast after the three-story computer the tower needed to operate its radar dish. After demolition is completed on the base, a project with a 2017 deadline, a plaque will commemorate the base and its defense mission during the Cold War.

Other Cold War-era bases still stand in North Dakota. The Finley Air Force Station sits derelict west of its namesake town, and is now a landfill for waste that will not decompose.

The Minot Air Force Station, another GCI base, was sold to a developer and is now a housing complex. The Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile Site near Cooperstown, N.D., offers tours and history of an area of intercontinental ballistic missile launch sites. The launch sites comprised a 6,500-square-mile area near the Grand Forks Air Force Base.

The most impressive of all military installations in North Dakota stands north of Nekoma, N.D.: The Stanley R. Mickelsen Safeguard Complex, complete with missile silos and a concrete radar pyramid. The site at one time held 46 long- and short-range nuclear missiles before it closed in 1976 after four months of operation. A Hutterite colony purchased the site in 2012.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Mystery of Writing Rock

On North Dakota’s northwestern prairie, about as far away from Fargo one can get in the state, sit two granite boulders shrouded in mystery.

Protected at a small park north of Grenora, N.D., Writing Rock State Historic Site, the boulders are inscribed with petroglyphs and markings from prehistoric Plains Indians. Carvings of thunderbirds are the most prominent on the boulders, and hundreds of years after their creation, their meaning is still not fully known. In Plains Indian culture, thunderbirds are creatures responsible for thunder and lightning and found in many stories. Theories abound around the boulders and the petroglyphs, which include connected lines and circles and other pecked markings.

Native culture says the boulders’ petroglyphs had future telling powers, abilities that were lost when whites moved the boulders. One story included in a mid-20th century Works Progress Administration state travel guide included a legend about the boulders.

“Many years ago a party of eight warriors stopped for the night near this rock, and just as they were falling asleep they heard a voice calling in the distance. Fearful of an enemy attack, they investigated but found nothing. The next morning they heard a woman’s voice calling, but still they found no one. In their search, however, they saw this large rock with a picture on it, showing eight Indians, themselves, with their packs lying on the ground. Unable to understand this mystery, the warriors went on their way.

On their return they again passed the rock and noticed that the inscription had changed, and appeared to hold a picture of the future. When they reached home they told their people of the mysterious rock, and the entire village moved near it, only to find that the picture had changed, this time showing the village with its tipis. From that time on the rock was believed to foretell the future until white men moved it; whereupon it lost its power.”

The smaller of the two boulders was held by the University of North Dakota for decades until 1965 when the state acquired Writing Rock. Several graves have been found in the region of Writing Rock, sites that included buried tools and beads, including one strand measuring 52 feet when strung together.

Despite the evidence of Writing Rock relating to Plains Indian culture, other theorists have attributed the boulders to European or Chinese explorers. Other writers suggest the boulders’ lines are maps. Most historians do not agree with these theories.

Writing Rock lies north of North Dakota Highway 50, lined with some of the least populated towns in the state, and south of the Fortuna Air Force Station, a Cold War-era radar facility all but completely demolished.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Roosevelt’s Recovery

Before actor Josh Duhamel, North Dakota’s only celebrity was Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th President of the United States.

Before his 1901-09 presidency, Roosevelt ranched and hunted in the western badlands of Dakota Territory. His 1883 bison hunt near the nascent town of Medora gave seed to his cattle ranching operations. Before he left the badlands in early fall that year with the hide and head of his bull bison, the 24-year-old politician gave $14,000 and a handshake to two ranchers to purchase a few hundred head of cattle from Minnesota.

What followed was a four-year stint of adventure and solitude on the edge of the American West for the young future president. Months after his badlands bison hunt, his wife and mother died on the same day, in the same house. Stricken by grief and shaken to his core, the young politician all but abandoned politics and buried himself in the badlands.

While out west, Roosevelt hunted. He wrote. He wandered. He lived the “strenuous life” of a cowboy and gained the respect of his neighbors for his efforts and fortitude. Roosevelt also acquired the physical and emotional strength that would stay with him for life.

He also saw the need for wildlife conservation. During his presidency, he set aside over 230 million acres of land for federal protection. Some of those spots are in North Dakota, such as the national wildlife refuges at Chase and Stump Lakes. The latter is underwater due to Devils Lake flooding.

Roosevelt’s time in the badlands offered adventure in all aspects of western life. He bagged every species of big game animal on his hunts, from bighorn sheep to elk to pronghorn. He ranched cattle, but lost over $20,000 following the devastating winter of 1886-87. Roosevelt also wrote parts of several books, including an 1884 tribute to his first wife Alice that would be the last he ever wrote of her. She would disappear from his recollections after that, and he even left her out entirely from his 1913 autobiography.

His badlands sojourn also included the tale of capturing three thieves who stole his boat. Roosevelt and two ranch managers built a second boat, pursued the thieves on the frigid, ice-filled Little Missouri River and later arrested the miscreants before a grueling overland march of 45 miles to Dickinson, N.D., to justice.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Turtle Mountains Majesty

At the top center of North Dakota’s map sits one of its smallest geographic regions: the Turtle Mountains. More of a forested plateau than anything mountainous, the Turtle Mountains rise hundreds of feet above the surrounding countryside while straddling the U.S.-Canadian border.

The Turtle Mountains are home to a lot of natural (and some manmade) wonders in North Dakota. The International Peace Garden grows north of Dunseith, N.D. The gardens also straddle the international boundary while commemorating the two nations’ peaceful coexistence along the world’s longest unfortified border. Up to 150,000 flowers are planted annually at the gardens, where music and athletics camps draw in international students.

Lake Metigoshe is another magnet in the Turtle Mountains, a popular, scenic lake with high property values bringing its total value from $39 million in 2005 to near $300 million in 2013. The same year, Turtle Mountain Real Estate reported a lot of less than one acre for sale for $395,000. The lake’s popularity grew with a strong farm economy and interest from Bakken region oil workers. The Turtle Mountains sit on the far eastern edge of the oil-rich Bakken region.

Mystical Horizons, a modern day Stonehenge, stands on the Turtle Mountains’ western edge, overlooking the vast landscape to the west. The site’s six brick artwork structures comprise a solar calendar through which one can view the summer and winter solstices and autumnal and vernal equinoxes.

The mountains are also home to the Turtle Mountain band of Chippewa. Native folklore tells us one way the mountains may have got their name. When viewed from the south, the region looked like a turtle to 19th century Metis hunters from the Red River Valley, with its head pointing west. The plentiful painted turtles in the region are another possibility for its name. Another tale tells of an Ojibwa named Makinak, or Turtle, who walked the mountains’ entire length in a day. The Turtle Mountains measure about 40 miles across at their widest point.

The Turtle Mountain State Forest, Lake Upsilon and a scenic byway offer other adventures in the Turtle Mountains, decorated with deciduous forest and a wealth of wildlife.

________________________________________________________________________________________

River Village Remains

North of North Dakota’s state capitol lies another major city of sorts. The Double Ditch Indian Village, a sizable earthlodge village dating to the late 15th century, lies on the east bank of the Missouri River.

Mandans occupied the village for 300 years, one of up to nine villages that lined the area near the Heart River’s mouth. Up to 10,000 Mandans lived along the river between 1490 and 1785, when the village was abandoned due to a smallpox epidemic. The disease broke out through North America in the 1780s, devastating American Indian populations.

Explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark noted the abandoned Mandan earthlodge villages during their ascent on the river in fall 1804.

“(We) passed the upper of the 6 villages the Mandans occupied about 25 years ago this village was entirely cut off by the Sioux & one of the others nearly, the Small Pox destroyed great numbers,” Clark wrote of the Double Ditch Indian Village on Oct. 22, 1804.

The village earned its name from its surrounding trenches, though the site has evidence of four ditches, more than its name suggests. The fourth, outermost ditch is the earliest, evidencing the founding of the village. Up to 2,000 people in 160 lodges lived in this 22-acre area. Early houses were rectangular with gabled roofs. By the 1500s, this design switched to an earthlodge, a circular architecture including earth and branches.

The village’s third ditch totals 15 acres and held a smaller community than the outer ditch. These two ditches are visible only to magnetic data. The trenches’ upper parts have been obliterated over the last five centuries.

The inner ditches, however, are still visible, built after the late 1600s. The second ditch had up to 100 houses within its 12 acres. Up to 1,200 people lived there. The innermost ditch is the last evidence of settlement at Double Ditch Indian Village. At four acres in total area, the community within the last trench contained 32 earthlodges and about 400 residents, most of whom died in the smallpox epidemic.

The Mandans who lived here grew squash and beans, among other edibles, and hunted for other subsistence. The Mandans and Hidatsas sheltered and assisted Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery during the winter of 1804-05 along the Missouri River near today’s Washburn, N.D. At the time, the Mandan river villages were the westernmost outposts in America.

Today, Double Ditch Indian Village is a state historic site with standing plaques, a walking trail and stone shelter at the site. The village site, however, is eroding into the Missouri River. In November, the state legislature approved a $3.5 million project to shore up the river with 1,900 feet of riprap, building a jetty and installing other materials to protect the site and its eroding burial grounds.

The 2011 Missouri River flood ate away at the riverbanks, exposing the ancient burial grounds where a conservative estimate pegs up to 10,000 people are interred.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Fort Sauerkraut Defense

Pickled cabbage was the namesake for a defensive sod fort built in 1890 near Hebron, N.D. The fort was perhaps the most extreme reaction to rumors of Sioux sweeping west from the Standing Rock Reservation, though no attacks ever came.

While a band of Sioux did leave the reservation that November, half-starved and dispossessed, they had not “broken out,” as telegraph reports of the time said. But the settlers of west river North Dakota heard and believed otherwise and took action.

Almost immediately, the settlers stopped their farm labor. Men sent their wives and children by train to Bismarck. Young men rode across the prairie spreading the word of the impending Sioux attacks. Livestock were cut loose to fend for themselves. Wagon loads of people, including women, children, the elderly and the sick and even poultry, sped east across the rugged prairie to escape the coming Sioux.

Meanwhile, the rumors of Sitting Bull and his 6,000 painted warriors racing across the plains to kill anyone in their way forced Hebron settlers to fortify their community. Estimated to be in the middle of the Siouxs’ “warpath,” the settlers, led by two Indian military campaign veterans, got to work at building a sod bastion high on Cemetery Hill overlooking Hebron.

Built from the dry sod of the prairie and stolen railroad ties, Fort Sauerkraut was an elliptically shaped embankment measuring “over 100 yards in its north and south diameter and (embracing) almost half a city block in area,” the site’s sign reads today.

Ox teams plowed trenches while men armed with shovels and spades built up eight-foot-tall embankments from earth. Two trenches were dug: a deep one outside the three-foot thick sod wall, and a second, shallower one inside the fort. A small, 100-foot-long building existed in the middle of the earthen embankment, with railroad ties supporting the roof.

Meanwhile, scouting parties were sent to watch for coming Sioux and to send up a smoke signal as a warning. Some men dispatched to Heart Butte, about 20 miles to the south, but no one allegedly wanted to stay there because of rattlesnakes. While Fort Sauerkraut’s builders waited for Sioux attacks, a caravan of natives from the Fort Berthold Reservation rolled in, offering to help fight the Sioux as they feared Sitting Bull would conquer their tribes and force them to join him.

The white settlers and natives holed up together for days until word came there was no danger of attacks. People slowly returned to their homes, and Fort Sauerkraut was left on Cemetery Hill for years until it crumbled away.

But in 2004, an energetic group of locals rebuilt Fort Sauerkraut using the same materials as their forebears. Today the earthen structure continues to stand watch over Hebron as a memory of the past and panic of its settlers.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Up in the Killdeer Mountains

North Dakota has no mountains, but that didn’t stop somebody from giving the Killdeer Mountains their name. The flat topped buttes comprise an erosional outlier rising up to 700 feet above the surrounding former prairie, reaching over 3,300 feet above sea level at their highest point.

The Killdeer Mountains are a site of historical and geographical significance in North Dakota. In summer 1864, the largest armed conflict between the U.S. Army and Plains Indians occurred just south of the Killdeer Mountains. General Alfred Sully’s 2,200 soldiers attacked a Sioux camp of over 1,500 lodges and more than 1,600 warriors. Sully was on a punitive expedition to find and assault the Sioux responsible for massacres of white settlers in Minnesota in 1862. The Battle of Killdeer Mountain was part of his second expedition into Dakota Territory to locate and punish the Sioux.

Today the battlefield site is marked by the State Historical Society of North Dakota, but oil activity and other developments encroach upon the historic site.

The largest deciduous forest in southwestern North Dakota is found in the Killdeer Mountains too. Mainly aspen and oak, the Killdeers also support ash, elm, juniper and other tree varieties.

Medicine Hole, North Dakota’s most famous cave, is also found above one of the buttes. A staggering climb a little over a mile long takes hikers to the legendary site, which native folklore says is from where all life emerged. While not a true cave due to the way it formed, Medicine Hole is basically a large crack on the southern butte of the Killdeer Mountains. Spelunkers have explored it to over 170 feet deep, finding three holes plugged with rocks thrown from people up above. Throwing rocks into Medicine Hole and hearing them clatter down is part of the uniqueness of the site.

A draft can be felt at times coming from the cave, and it is thought to open up near a rattlesnake den 80 feet below on the southwest side of the Killdeer Mountains.

Since summer 2014, landowner Brian Benz has closed off access to Medicine Hole due to perceived injustices against him and other landowners in a land study of the Killdeer Mountain battlefield’s historic district.

Hikers shouldn’t be discouraged; the Killdeer Mountains Wildlife Management Area northwest of Killdeer, N.D., offers adventures in the rugged countryside, though camping is prohibited on Tuesdays and Wednesdays.

Meanwhile, the development of the oil-rich Bakken region led the Killdeer Mountain Alliance to advocate for the preservation of the mountains’ “cultural, spiritual, ecological, archaeological and historical integrity.” The group has sought conversation on the installation of mega power poles, a water tower and other developments near the battlefield site and natural beauty of the Killdeer Mountains.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Jews on the Prairie

One of the little known and least populous ethnicities to emigrate to North Dakota were the state’s Jewish settlers. Beginning in 1882, Jewish emigration to North Dakota began with six colonies and farming attempts throughout the state. Many Jews to North Dakota hailed from Poland or Russia, escaping persecution and dim futures. Russian Jews were forbidden to own land, which did not help their sustainability on the Dakota prairie.

German Jews already settled into America’s economy feared for anti-Semitism with the wave of Jewish immigrants coming to America. They urged them to go west where they could work cheap or essentially free land provided by the Homestead Act. Eastern European Jews tried their hand at farming and life on the prairie, beginning at the Painted Woods colony, established in summer 1882.

Painted Woods was a Jewish settlement about five miles south of Washburn, N.D., near the Missouri River. Forty settlers originally comprised Painted Woods, advertised as “The Russian Jewish Farming Settlement.” By 1884, over 50 families called the settlement home. The St. Paul Globe reported in fall 1884 that “we were pleased to observe that no disputes of importance appear to have arisen amongst the colonists, who, in spite of the undoubtedly severe struggles incidental to their life, professed themselves very contented with their lot, and very grateful for what had been done for them.”

However, by the 1890s, the Painted Woods colony had largely disbanded. North Dakota State’s Institute For Regional Studies put the Jews’ failure on a “lack of agricultural know-how, lack of capital and crop losses due to hard winters, hail, drought, infestations and poor prices.”

Jewish homesteaders also settled near Garske, N.D., north of Devils Lake, where all that remains today is Sons of Jacob Cemetery, a small graveyard dating to 1883. Rachel Calof, a Russian Jew who settled near Devils Lake in the 1890s on the “limitless” prairie, wrote a biography of her experiences that chronicles her life homesteading in the Devils Lake area. NDSU’s HIST 220: North Dakota History class uses Calof’s book as course material.

The Regan-Wing area in central North Dakota also experienced a boom in Jewish settlers around 1900, but this settlement declined as well. A small cemetery near Regan is all that remains of these Jews, who were prosperous enough to give thought to building a synagogue. The structure was never built.

Other Jewish settlements sprang up in the Ashley-Wishek area, where David Berman, a Jewish American mobster was raised before his family failed in working the land before moving to Iowa. Berman was nicknamed “Davie the Jew,” held gambling operations in Las Vegas and died in 1957 during surgery to remove colon polyps.

Other Jewish colonies developed near Marmarth and Flasher, N.D., but these settlements generally failed as well.

Today about 400 Jews live in North Dakota, or one-twentieth of a percent of the state’s population. North Dakota has three synagogues in Bismarck, Grand Forks and Fargo; however, only the latter two are active while the Bismarck synagogue has been renovated by two Christian ministries for headquarters.

Cannonball concretions also range from Kansas’s Rock City park to New Zealand’s Moeraki Boulders.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Cannonballs on Battleship Butte

While eastern North Dakota is mostly flat farmland and rolling hills, the state’s western reaches are a geologist’s dream.

From the weathered layers of the badlands to a petrified forest to fossilized dinosaurs, western North Dakota is a stroll through 65 million years of geology. One spot in the North Unit of Theodore Roosevelt National Park is home to cannonball concretions, hard geologic formations surrounded by soft rock and strata.

At Cannonball Concretions Pullout along the park’s 13-mile scenic auto route, visitors can ogle at the spherical concretions formed from groundwater.

“Concretions form by the selective precipitation from groundwater of dissolved minerals, most commonly calcium carbonate, the stuff of which limestone is made … As these minerals precipitate, they fill in pore spaces between grains of sediment thereby cementing them together,” the North Dakota Geologic Survey wrote.

Concretions can be any shape and size, from enormous log shapes to smaller spheres. Concretions are found throughout southwestern North Dakota. The Cannonball River, which forms the northern boundary of the Standing Rock Reservation, takes its name from the concretions found along its banks.

The cannonballs along the North Unit’s scenic route are easily accessible. Many are exposed or eroding out of Battleship Butte, the soft rock formation at Cannonball Concretions Pullout.

Other concretions in North Dakota are found near Oxbow Overlook in the North Unit and in the backcountry of the park’s South Unit north of Medora, N.D. Others are on the shores of Lake Sakakawea, the reservoir created from the dammed waters of the Missouri River in western North Dakota. More cannonball concretions are found throughout Morton and Sioux counties, and they even decorate the entrance to Bismarck’s North Dakota Heritage Center.

Cannonball concretions also range from Kansas’s Rock City park to New Zealand’s Moeraki Boulders.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Drained of People

North Dakota has an all-time high for its population. The Census Bureau pegged the number of state residents at 756,927 last year, up by over 110,000 people from 2005.

The state’s population is historical a cyclical one of ups, downs, booms and busts. The Great Dakota Boom between 1878 and 1890 saw the population of modern North Dakota jump from 16,000 to 191,000, North Dakota Studies found. The Homestead Act and arrival of the railroad were two major factors.

By 1900, nearly 320,000 people called North Dakota home. In 1930, the state saw a high of 682,000, but the ’30s were also devastating. Severe drought and crop failure forced the state onto federal relief. From 1933-35, North Dakota received $25 million in aid ranging from work relief, emergency education and college student aid. One in three North Dakotans received Federal Emergency Relief Act aid money by spring 1934. That year, the state also led the nation with the highest percentage of residents on federal relief. By 1940, over 40,000 people had left the state.

The next 60 years were a struggle for the state as its population seemed to drain away. Barely 620,000 people remained in 1970, and 2000 saw less residents than 1930. The state lost 4,000 people annually from 2000-04, mainly young people who departed to seek their fortune elsewhere.

However, the 20th century did see some growth. Oil booms in the 1950s and ’80s brought brief growth, but quickly withered away.

Cities and towns that once held hundreds of people had only a handful of residents by 2000. Many today still have only a few dozen.

Marmarth, N.D., is an extreme example; over 1,300 people lived there in 1920. Today, not even 150.

The cycle of growth and out-migration continued into recent years. With the discovery of the Parshall oilfield in 2006 and new developments in technology to recover oil of the Bakken region, North Dakota saw another energy rush. Thousands flocked to the state’s western reaches where cities like Williston, Watford City and New Town exploded in numbers.

Growth of Fargo as a technology hub also drew people to the state. The city is home to Microsoft’s second largest campus after Fargo businessman Doug Burgum sold Great Plains Software to Microsoft for $1.1 billion in 2001.

Census Bureau predictions peg North Dakota clinching 1 million residents as soon as 2040. This estimate comes after the Buffalo Commons, an ecological proposal of the ’90s that offered a different solution to North Dakota’s and other states’ agricultural sustainability: return the drier plains to native prairie for bison to graze upon to counter rural depopulation and farm failure.

Despite North Dakota’s recent oil boom and statewide growth, many ghost towns and nearly empty communities dot the state map. Just 33 of North Dakota’s 357 cities have over 1,500 residents.

________________________________________________________________________________________

The Man Camps

North Dakota’s oil boom in the mid-2000s triggered a rush of growth in the state’s western region. An explosion of people and traffic exhausted western North Dakota’s towns and roads, leading to housing woes, overworked infrastructure and rising crime. Williston, the city at the heart of the oil-rich Bakken region, swelled from 12,000 people in 2000 to over 33,000 by 2014. The city’s limits tripled in size by 2013.

To combat the Bakken’s housing shortage, civic leaders and oil companies chose a short-term solution that lasts to this day: workforce housing, or man camps. Bunker-style, identical units began to cover the outer limits of cities like Williston and Watford City as subdivisions and apartment complexes went up. Water and sewer systems had to be dug as well, forcing Williston and Watford City to rack up millions of dollars in debt to finance new infrastructure.

For the workers who came to North Dakota’s Bakken region, man camps proved to be one of the few options for housing. The camps bred loneliness and boredom as many workers lived away from their families. Meeting women also proved hard in west Dakota counties, where three years ago, the New York Times reported 1.6 young, single men for every young, single woman.

Violence came with the man camps too. A Michigan man stabbed his lifelong friend to death in a Tioga camp in 2013. A Texas man shot two people, killing one of them in another Tioga man camp in 2012.

Last year’s slumping oil prices hit the Bakken region hard as rig counts dropped drastically and workers lost their jobs. The decline also hit the man camps. Operating permits for 23 man camps in Mountrail County expired last year, and only five applied for renewal. Man camps beds in Williston totaled 3,000 last fall, up to 70 percent of which were occupied. Target Logistics, a housing business, set a goal in early 2012 to “house 1 percent of North Dakota’s population” by the end of that year.

North Dakota sweet crude hit an all-time high of $136.29 a barrel in summer 2008; prices last month stood at $17.25 a barrel, as Flint Hills Resources reported.

The hardest hit to North Dakota’s man camps came late last year when the Williston City Commission approved an ordinance denying occupancy permits to man camps beyond July 2016.

“The man camp industry should understand we allowed them to come here on a temporary basis,” Williston Mayor Howard Klug told Reuters, adding the city may make an amendment allowing some man camps to keep functioning.

With new developments and apartments, Williston city leaders said they want workers to put their roots down in Williston, something man camps can’t offer.

“The reason for them has gone away,” Mountrail County’s planning administrator told the Bismarck Tribune last fall.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Ukranian Remains

Of all the immigrants and ethnic groups that settled in North Dakota, Ukrainians are one of the most interesting. While every European ethnic group emigrated to North Dakota, and their separate struggles are by no means diminished, the state’s Ukrainian pioneers are an intriguing chapter.

The first Ukrainians settled North Dakota in the Belfield area in 1896. They came from Galicia in western Ukraine, a region then under Austro-Hungarian control. Most western Ukrainians came to North Dakota via Winnipeg on advice that the state was better for settlement. Ukrainians settled North Dakota not even a decade after its statehood, a time when much of the Dakotas had yet to be homesteaded.

Other Ukrainian settlements in western North Dakota sprang up at Gorham and Ukraina. Many of these Ukrainians were Eastern Catholics who followed the Byzantine rite. Churches of theirs still stand today, though not in their original locations. St. Demetrius Ukrainian Catholic Church was moved from Ukraina in the 1950s, as was Sts. Peter and Paul Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Thatched roof houses also once stood at Ukraina, which disappeared when settlers left for Belfield and elsewhere in the ’50s.

Two other Ukrainian churches stand at Wilton, N.D., with Sts. Peter and Paul Ukrainian Catholic Church dating to 1890. Another Ukrainian orthodox church stands in Pembina, N.D.; it closed in 1987 but was later restored by the city.

The post office at Grassy Butte, N.D., built of earthen materials also stands as another extant Ukrainian structure in the state. It served Grassy Butte from 1914 to 1962 and joined the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 as “one of the last known examples of Ukrainian-type log and clay plaster construction in North Dakota.”

Ukrainians also settled near Max and Drake, N.D., along the railroad. These Ukrainians were Protestants leaving their home country in opposition to the Russian Orthodox Church. The Protestant Ukrainians were a mix of Baptists and Seventh Day Adventists.

A cross erected in 1902 on a hill north of Belfield memorializes North Dakota’s Ukrainian pioneers, who with their descendants numbered about 2,000 in the Belfield area in 1950.

“They emigrated from the ‘bread basket’ of Europe to the virgin sodland yet untouched by man — from a region of warm climate to an area where long winters lay life dormant,” the sign reads. “Yet within a span of a lifetime, they developed here in Dakota a farming empire undreamed of by man.”

The Ukrainian Cultural Institute preserves the ethnicity’s culture in North Dakota today with numerous events throughout the year, including Easter egg decorating, an annual dinner and folk festival.

“They escaped dire poverty, and came over here and also experienced dire poverty,” said one Ukrainian descendant in a documentary about the homesteaders, ” … but they had … a great sense of hope.”

________________________________________________________________________________________

Sullys Hill’s Story

A massive, monstrous lake is not the only natural curiosity at Devils Lake in northeastern North Dakota.

Sullys Hills National Game Preserve, a wildlife refuge and nature center, is a jewel of Mother Nature. Three landscapes meet at this former national park established by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904. It was decommissioned to a national game preserve in 1921, owing to its remoteness.

In 1909, a Department of the Interior report found that Sullys Hills National Park had no good road access, no buildings, no budget and no improvements. The national park also lacked staff, though a Fort Totten boarding school employee “was keeping an eye on” Sullys Hill. The park lay two miles away from the closest riverboat landing. The park also suffered from low visitation — about 250 people annually.

The history of the Sullys Hill area alone is far-reaching. The refuge lies on the Spirit Lake Reservation, established in 1867 by treaty and headquartered at the town of Fort Totten, N.D. Fort Totten, the former military post and boarding school, still stands, built from local brick in 1868. The fort is now a state historic site.

Sullys Hill offers a variety of wildlife, ranging from bison to elk to 270 bird species. The refuge offers hiking, including a steep trek up Sullys Hill to a lookout point over the lake, forest and grassland. The game preserve totals 1,674 acres.

Sullys Hill’s geology is also an interesting story. A south-moving glacier moving across eastern North Dakota ran over an aquifer pressurized by a layer of permafrost. The advancing glacier increased the aquifer’s water pressure, leaving no room for water to escape but up. The water’s upward movement forced materials into the path of the glacier, pushing the materials south. After the materials moved away, a depression was left under the glacier, and an ice-thrusting event occurred, creating Sullys Hill and other moraine hills from the material the glacier scooped up.

Sullys Hill is specifically comprised of brecciated shale and glacial sediment from Devils Lake’s main bay. The prominent hill sits at about 1,740 feet above sea level. Sullys Hill is one of several hills in a series of ice-shoved ridges along the closed basin that is Devils Lake, a natural lake with no natural outlet that has grown seven times in volume since 1993.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Shadows of Schafer

Not much is left of Schafer, N.D., except for a few scattered outbuildings and a dirt road. The ghost town, the former McKenzie County seat, has its place in North Dakota history as the jail where Charles Bannon, the last person lynched in the state, was seized and later hanged off a bridge.

North Dakota and Dakota Territory have 11 documented lynchings since 1882. Bannon’s death in 1931 came after a series of written confessions to killing six members of the Haven family in winter 1930. In an argument with Daniel Haven, Bannon allegedly “accidentally” shot the 18-year-old and later shot to death the other five family members out of fear, he said in his confession. Bannon, 22, had been a farmhand on the Havens’ farm.

He allegedly buried the bodies in various spots, including hiding 2-month-old Mary Haven’s corpse in a straw pile. Bannon also reportedly dismembered Lulia Haven because she was too heavy to carry.

Bannon’s father joined him on the farm soon after the killings. They worked the Havens’ farm until the fall when Bannon began selling the family’s crops and property, attracting scrutiny. Meanwhile, his father had gone to Oregon where Bannon had said the Havens went, and later wrote a letter to his son telling him to “do what is right.”

Later that month, grand larceny charges landed Bannon in jail. County authorities discovered the Haven murders. Bannon confessed in writing to his involvement in the killings, which be blamed on a “stranger.”

Bannon later solely confessed to the murders. Authorities extradited his father to North Dakota on murder complicity accusations. Bannon wrote a final confession in January 1931, alleging he acted alone in the murders, claiming he killed the Havens out of self-defense and fear.

On the night of Jan. 28-29, 1931, Bannon, his father, a deputy sheriff and another inmate were present in the Schafer jail when 80 masked, armed men rolled up in 15 cars. They battered down the jail’s front door, overpowered the deputy and took his keys before escorting him away from the jail. After nearly giving up at trying to break down Bannon’s cell door, the mob placed a noose around Charles Bannon’s neck and dragged him away.

The mob drove to the Haven farm where the caretaker chased them off the property. The men then drove to a new bridge over Cherry Creek near the jail. Bannon was dropped over the side of the bridge, snapping his neck. The mob dispersed. None of its members were identified or arrested.

The town of Schafer suffered following Bannon’s illegal execution. The county seat moved to Watford City in 1940. Many of Schafer’s buildings were moved there. Today the Schafer’s silent stone jailhouse is nearly all that remains, surrounded by oil activity and the grim shadow of the ghost town’s short history.

________________________________________________________________________________________

A Land Before Time

Nothing in North Dakota is as alien as a petrified forest.

On the western edge of Theodore Roosevelt National Park’s South Unit, two petrified forests lie in secluded badlands. Stumps, trunks and various pieces of former coniferous trees lie scattered across the rugged landscape, accessible via hiking trails.

The trees, ancestors of today’s cypresses, stood up to 100 feet tall. Their stumps are all that remain of the swamps that were the badlands over 55 million years ago. As floods inundated this environment, the stumps were buried while the trees fell and decayed.

Over time, the trees’ stumps and other remains were petrified as minerals gradually replaced organic material following the tree’s rapid burial under silt and sand.

The effect left a scattering of thousands of petrified stumps and other remnants of the old trees, strewn across the badlands and other places. Petrified forests can also be found near Lake Sakakawea in Mercer County and near Taylor, N.D.

Farmers in western North Dakota find petrified wood to be as common as rocks eastern North Dakota farmers pick from their fields. The wood is used in landscaping, as lawn ornaments and in signage and memorials, such as a World War I and II monument in Amidon, N.D.

The petrified forest within Theodore Roosevelt National park is extensive and ideally accessible in autumn when the weather is more conducive for hiking. Rattlesnakes, heat and greasy bentonite clay are hazards in summer and spring, along with snow and cold in winter.

A high concentration of petrified wood is found along a trail beginning at a parking lot at the end of a gravel road leading several miles off of Interstate 94. The road is used by the state’s oil industry and several pumpjacks and gas flares are visible along this 7-mile stretch of red road.

Few places in North Dakota offer a glimpse into the ancient past like Theodore Roosevelt National Park’s petrified forest, where millions of years take the shape of stumps.

________________________________________________________________________________________

BURNED OUT

Many small North Dakota towns have suffered declining populations and abandonment over the years as residents moved to larger cities. One town lost nearly everything in one day.

Shields, N.D., a small town on the Cannonball River south of Mandan, went up in flames in July 2002 as four grass fires raged across the Grant and Sioux counties. The largest of the fires burned 10,000 acres, racing across the dry, hot, grassy landscape and destroying 30 buildings in Shields, displacing its 15 residents.

In an age when cell phones were not as popular, residents of the region were given minutes’ warning to evacuate the area as for some; word only traveled door to door. The Shields blaze left all but three buildings untouched — its bar, post office and one home.

Battling the fires attracted enormous efforts from volunteer, local, state and federal agencies.

Two National Guard helicopters dumped Missouri River water over the fires, 200 gallons at a time. On the ground, fire crews worked to contain the flames, some up to 25 feet high.

“Everyone with a hose showed up” to fight the fires, an emergency management official said at the time.

In the days after, hot spots still remained in some areas. Fire officials estimated a lightning strike igniting extremely dry grass started the blaze.

Other grass fires at the time destroyed barns at Cannon Ball, N.D., and raced across grasslands near Fort Yates, N.D., and Kenel, S.D. Efforts took two days to extinguish the fires.

As for Shields, all that remains today are charred remnants of wood and bricks and several open basements. Shields lies in a lonely region of North Dakota home to several sparsely populated and abandoned towns.

Despite losing near everything, Shields residents kept a positive outlook on the future of their town.

“If there’s a post office and a bar, a community will survive,” a resident said in the days after Shields burned.

________________________________________________________________________________________

FORT ON THE RIVER

North Dakota’s written history is quite young in the scope of the U.S., with its earliest records dating back two and a half centuries. One of the earliest sites established in what would become North Dakota predates the state’s status as Dakota Territory.

Fort Abercrombie, a military fort on the Red River, was established in spring 1857 as the first permanent military base in modern North Dakota. Trade among Canada, the Northwest and Minnesota necessitated a military presence, as did the settlement of Minnesota and the Red River Valley.

Fort Abercrombie sits at the head of navigation on the Red River, north of where the Bois de Sioux and Otter Tail Rivers meet in a confluence to form the Red. The fort’s protection allowed new and old trade routes to operate in what was then a hostile prairie.

The Dakota Conflict of 1862 boiled over from Minnesota, as Sioux warriors killed white settlers and two U.S. Army expeditions mounted campaigns to find and punish the Sioux.

Fort Abercrombie offered protection for settlers and traders, but had little to physically guard the military fort.

At the time, no walls or blockhouses were constructed at Fort Abercrombie. Once word of the Sioux attacks reached the fort, troops began erecting wooden stockades.

A teenage boy living at the fort at the time described it as, “Fort Abercrombie at this time, was a Fort only in name, it consisted of a lot of buildings, and the only thing in the shape of defence (sic) was a breast-work of Cordwood built around the flag staff which stood in the center of the square, inside of which were placed three, twelve pound, Howitzers, the only guns the Fort contained.”

Fort Abercrombie included a barracks, guardhouse, hospital, ferry crossing, stable and other structures. The fort lay under siege by Sioux for 60 days until reinforcements from Fort Snelling in Minnesota arrived.

In 1877, Fort Abercrombie was abandoned as the Red River Valley drew settlers to cultivate its fertile soil. The fort’s buildings were later sold and relocated. A Works Progress Administration project in the 1930s reconstructed, restored and returned many buildings to the fort site, where today an interpretive center, picnic area and Richland County Road 4 are the only modern updates.

________________________________________________________________________________________

REACH FOR THE SKY

North Dakota has few claims on a global scale, but the third flattest state in America does have bragging rights to the tallest structures in the western hemisphere.

The KVLY-TV mast west of Blanchard, N.D., stretches 2,063 feet into the sky. The television transmitting mast was constructed in summer 1963 and is used by local TV station KVLY to transmit its Channel 11 broadcast over 9,700 square miles.

For many nonconsecutive years, the KVLY-TV tower was the tallest man-made structure on earth. A Poland radio mast surpassed North Dakota’s mast in 1972, but fell in a guy-wire exchange in 1991.

Until 2010, the mast was again the tallest structure in the world. The completion of the Burj Khalifa, a 163-floor Dubai skyscraper, edged out the KVLY-TV tower, as did a Tokyo steel tower and a Shanghai skyscraper in 2012 and 2013, respectively.

Today the KVLY-TV tower is the fourth tallest structure in the world, but the tallest guyed mast on earth. The mast’s sister to the south, meanwhile, is the planet’s fifth tallest structure.

The KRDK-TV tower is three feet shorter than the KVLY mast, but unlike its sister, it has collapsed. The 2,060-feet mast first fell in 1968 when a helicopter severed some guy wires, killing the four people onboard the aircraft. The tower fell again in spring 1997 when wind and ice brought it down in Blizzard Hannah, the storm that preceded the Red River flood of 1997.

Sticking up out of flat farmland in the Red River Valley, the KVLY-TV tower is fairly isolated in rural Traill County. From its top, one can see for dozens of miles in every direction, owing to the flatness of the Red River Valley. In 20 minutes, an elevator can take two people to the point under the mast’s 113-foot transmitting antenna.

Since its construction, the Federal Communications Commission and Federal Aviation Administration made policy regulations prohibiting masts taller than 2,000 feet, except in “exceptional cases.” Outside of North Dakota’s two transmitting masts, the U.S.’s next tallest structures are another mast in California and an offshore oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico.

________________________________________________________________________________________

REMOTE ROCK ART

On a rocky hill overlooking the rolling countryside of Grant County sits one of the oldest, most remote historic sites in North Dakota.

Medicine Rock, an ancient religious shrine of the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes, is a large sandstone outcrop covered with petroglyphs, pictographs and other images by natives who looked to the rock as an oracle. The site was a gathering space before buffalo hunts where the tribes would dance, make offerings of tobacco and hold smoking ceremonies.

The rock’s many pictures and carvings depict many figures, from hoof prints to a turtle to bird tracks. The clairvoyant hieroglyphics are said to have appeared from the Great Spirit’s acceptance of a person’s offerings after a smoking ceremony and washing of a part of the rock. Army explorer Stephen H. Long’s expedition wrote of Medicine Rock’s powers in an 1819 journal entry.

“Upon the part of the rock, which (a person) had washed, he finds certain hieroglyphics traced with white clay, of which he can generally interpret the meaning,” Long’s expedition wrote. “These representations are supposed to relate to his future fortune, or to that of his family or nation; he copies them off with pious care and returns to his home, to read from them to the people, the destiny of himself or of them.”

Medicine Rock is still a sacred site in American Indian culture. Offerings of tobacco and cloth can be found tied to the chain-link fence that surrounds the outcrop. Evidence of ancient powwows is still visible in a dark ring just west of Medicine Rock, where thousands of people flocked for dance ceremonies. Tribes held feasts near Medicine Rock as well. Long’s party wrote that the Hidatsas traveled up to three days from their villages to reach the sacred site.

Of the six American Indian rock art sites owned by the State Historical Society of North Dakota, Medicine Rock is the largest. Its location south of Elgin, North Dakota, is well off the beaten path, down several dirt roads and across private land. In the rugged countryside of Grant County, Medicine Rock is a highlight among conical hills and a vast horizon.

________________________________________________________________________________________

FLAT, FLAT, FLAT

One of the planet’s flattest landscapes covers the entire eastern edge of North Dakota.

The Red River Valley, the lakebed of ancient Lake Agassiz, is an immensely flat, incredibly fertile area of land. The lake was born from ice melting northward during the last ice age. Lake waters drained away 9,300 years ago, exposing land in the sediments left behind. That soil, up to 60 feet deep in places, is some of the most fertile on earth.

The region measures 320 miles long by 50 miles wide in North Dakota, Minnesota and Manitoba.

The landscape’s name is a misnomer; the Red River Valley is no valley, but an ancient lake bed. The true Red River valley is about 100 feet wide. The north-flowing river drops about 250 feet from its headwaters in Wahpeton, N.D., to its mouth in Lake Winnipeg. In east-central North Dakota, the river drops about 5 inches per mile; that gradient decreases to 1.5 inches per mile in Pembina County, North Dakota’s northeastern corner county.

The landscape’s flatness lends itself to immense overland flooding. Early white settlers to the region were just about washed off the land in the flood of 1826. The flood of 1897 nearly destroyed Fargo, and a century later, the flood of 1997 inundated Grand Forks and East Grand Forks, Minnesota. Grand Forks’ mayor ordered the evacuation of 50,000 people, the largest exodus of an American city since the Civil War.

The Red River saw its greatest flood in 2009. The river topped its 1897 record with a measurement of 40.84 feet. Despite damages from overland flooding around the Red River Valley, the city of Fargo rallied against the floodwater rather than evacuating the area.

Overland flooding and a lack of topography haven’t kept people from populating the region. Eastern North Dakota and the Red River Valley are home to a majority of the state’s population, as well as a vastness of farmland. The Red River Valley’s fertile soil is an agricultural paradise, producing sugar beets, corn, soybeans, wheat and other crops.

________________________________________________________________________________________

GORGEOUS

Most scenic views in North Dakota are best found in the state’s western region, atop buttes and badlands. But eastern North Dakota, flat as a tabletop, has its overlooks, too.

Just head north.

The Pembina Gorge lies in the state’s northeast corner, as the state’s longest, deepest, unaltered river valley. Glacial meltwaters created the gorge over 9,000 years ago as they emptied into Lake Agassiz, the lakebed of which is the Red River Valley.

Today, the gorge is rich with deciduous forest, grassland and nearly 500 species of plants. The region is one of the few remaining wilderness areas in North Dakota.

The Pembina River, running through the gorge, is North Dakota’s only white water river. Kayaking and canoeing are popular on the river, which meanders among native trees and farmland on its way to join the Red River at Pembina, North Dakota, just south of the state’s lowest point where the Red River drains into Manitoba.

The Pembina Gorge is popular year-round with snowboarding, skiing, hiking, bird watching and photography all available. Several scenic overlooks sit atop the gorge just west of Walhalla, North Dakota, the state’s second oldest town. The Pembina Gorge lies in the Rendezvous Region, an area stretching from Pembina to Walhalla and Cavalier to Langdon. Over 200 years ago, Canadian fur trappers and locals traded in modern northeastern North Dakota.

North Dakota’s first known white traveler, Pierre Gaultier de la Verendrye, found his way into the state in 1738, in the Pembina Gorge region. His and his sons’ explorations covered North Dakota in the 1730s and ’40s, from the Missouri River to the southwestern badlands.

Among other claims, the Pembina Gorge is home to the state’s only indigenous elk, North Dakota’s oldest house and unique views atop its glacially carved valley.

Not all of eastern North Dakota is flat.

________________________________________________________________________________________

BADLANDS & GRASSLAND

Rolling hills and flat plains formerly blanketed the state until agriculture developed the land for farming purposes. The state’s sub-humid grassland is a fragile ecosystem, and few uncultivated areas remain.

But they’re still out there.

The Little Missouri National Grassland contains more than 1,600 square miles of native mixed grass prairie in western North Dakota.

The grassland stretches north-south between Marmarth and Williston, conserving some of the most rugged and beautiful country in North Dakota. Colorful badlands along the Little Missouri River paint the landscape with red, purple, blue, brown, gold and other colors of sediments laid down thousands of years ago, stripped away by wind and water.

The Little Missouri National Grassland is open to public use, including hunting, camping, bird-watching and other outdoor recreation. The Maah Daah Hey bike trail runs northward from the Burning Coal Vein near Amidon to the North Unit of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, across 96 miles of badlands.

The weather fluctuates dramatically on the Little Missouri National Grassland, with sweltering summer heat and bone-chilling winter weather sinking well below zero. President Theodore Roosevelt ranched on the modern grassland in the mid-1880s, losing most of his cattle in the deadly winter of 1887.

One rancher’s letter to his superior that winter summed up the blanket of depression the season brought to the badlands: “No news, except that Dave Brown killed Dick Smith and your wife’s hired girl blew her brains out in the kitchen. Everything’s OK here.”

Today the Little Missouri National Grassland is highly active with oil and gas development of the Bakken region. Along with the Cedar River National Grassland in south central North Dakota and the Sheyenne National Grassland in the state’s southeast corner, national grasslands make up less than 2.5 percent of North Dakota’s area.

________________________________________________________________________________________

MARKS ON MEDINA

Medina, North Dakota, population 306, sits alongside Interstate 94 with relatively little to see on its surface. That’s because the city’s history holds most of its intrigue.

In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt established Chase Lake National Wildlife Refuge, a bird sanctuary that sits a few miles northwest of Medina, the home of the refuge’s visitors center. Chase Lake is a remote alkali lake with two islands amid prairie wetlands that sees a third of the continent’s American white pelican population.

The lake hosts the largest nesting colony of pelicans in North America, with estimates of up to 50,000 pelicans at the lake in 2013.

Chase Lake draws visitors, bird watchers and photographers into the Medina area. The American Bird Conservancy places Chase Lake among the top 100 globally important bird areas in the U.S.

Medina’s history also holds one of North Dakota’s most infamous crimes.

Gordon Kahl, a Heaton, North Dakota, farmer, was a leading member of Posse Comitatus, a paramilitary group of vigilantes who opposed government authority, most notably tax collection. In 1977, he served an eight-month prison sentence for a tax evasion conviction.

On Feb. 13, 1983, Kahl, his wife, son and three supporters were leaving a township meeting in Medina when U.S. Marshals made moves to arrest Kahl for an alleged parole violation. Federal and local authorities made a roadblock on the highway north of Medina, where an ensuing shootout took place.

Kahl and his son armed themselves with Ruger Mini-14 rifles. The six lawmen pursuing him were armed with shotguns, handguns and semiautomatic rifles. Kahl killed two U.S. Marshals in the firefight, and four people were wounded, including Kahl’s son.

Kahl fled in a police cruiser and was killed in another shootout in Arkansas four months later. His crimes in central North Dakota, particularly the Medina shootout, are still vivid in local history.

________________________________________________________________________________________

BATTLEFIELD BLOODSHED

North Dakota’s deadliest battle between whites and Native Americans played out at Whitestone Hill in September 1863.

Generals Alfred Sully and Henry Sibley headed campaigns in 1863 to punish the Sioux responsible for murders in Minnesota in 1862. As Sibley headed west with 2,000 men, the conflict spilled into Dakota Territory. His troops fought three brief skirmishes with Sioux warriors in late July before turning back to Minnesota, their excursion a failure.

Sully, meanwhile, was marching north from modern South Dakota and discovered an encampment of several Sioux tribes. About 700 of Sully’s 1,200 men were present for the ensuing battle against hundreds of warriors. Thousands of Sioux women and children were also in the camps.

Sully’s men attacked, intending to corral the Sioux while cutting off escape routes.

The close quarters battle claimed many Native American lives.

White soldiers recalled Sioux warriors raiding the battlefield at night and scalping American troops while they wailed and cried.

Many Sioux escaped during the sunset battle, abandoning their homes and goods. Sully ordered his troops to destroy everything, including 300 teepees and over 200 tons of buffalo meat. These supplies and more were the Sioux stores for winter, and their destruction left the tribe destitute for the coming season.

Two days after the battle, a patrol of two dozen soldiers found a few hundred Sioux several miles from Whitestone Hill. The Native Americans chased the small group back to the battlefield, killing and wounding several of the soldiers along the way.

Twenty soldiers were killed in total, while Sioux losses were estimated between 100 and 300. Over 150 Sioux men, women and children were captured. Sully called the battle a victory, despite killing Sioux warriors who likely had no part in the Minnesota uprising.

“I believe I can safely say I gave them one of the most severe punishments that the Indians have ever received,” Sully said.

________________________________________________________________________________________

GARRISON DAM DESTRUCTION

One of the planet’s largest dams forever altered the heart of North Dakota’s Fort Berthold Indian Reservation.

The Garrison Dam, the world’s fifth largest rolled earth dam, flooded the rich Missouri River bottom lands of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara tribes when its construction was completed in 1953.

Thirteen men died in the process of building the dam that would form the reservoir later called Lake Sakakawea, but the losses didn’t stop there.

Two thousand people, mainly Native Americans, were displaced by the rising waters of the reservoir. Forced to flee to higher ground, the soil they found was unsuited for their farming lifestyle. The towns of Sanish, Van Hook, Charging Eagle, Elbowoods and others slipped under the reservoir.

About 900 residents of Sanish and Van Hook decided to form a new town on higher ground. The names Sanhook and Vanish were thrown around, the latter an ironic suggestion for a town replacing two lost underwater. Eventually the name New Town stuck, because that’s what it was.

When the floodwaters reached 1,850 feet elevation, the reservoir was filled.

The Garrison Dam holds back more than 7 trillion gallons of water today in Lake Sakakawea. The dam generates hydroelectric power for over 300,000 homes and stretches over two miles between the lakeside cities of Riverdale and Pick City.

The Garrison Dam is often added to the list of injustices against North Dakota’s Three Affiliated Tribes, who were forced to accept government compensation for their land or face confiscation by eminent domain.

An overlook park, downstream campground, Pick City’s Dam Bar and other attractions await visitors at the Garrison Dam, both an engineering feat and a source of heartbreak in North Dakota.

________________________________________________________________________________________

LET PEACE PREVAIL

International Day of Peace is on Monday, and nowhere in North Dakota is the holiday better to observe than at the International Peace Garden.

North of Dunseith on the Canadian border, the enormous park was dedicated in 1932 to celebrate the peaceful coexistence of the US and Canada. Gardens and manmade lakes straddle the international boundary.

The Peace Towers, two pairs of 120-foot concrete columns, stand on either side of the border, mere feet from each other. The towers were erected in 1982 and are now crumbling apart. They will be torn down before 2016; a replacement structure has yet to be planned.

Horticulture is the main visual attraction of the International Peace Garden. Over 150,000 flowers are planted annually. An indoor cacti observatory draws visitors year-round. Fountains and waterworks pulse throughout the gardens, and several hiking trails are available, along with a campground, gift shop and picnic areas.

A recent addition to the peace garden is a 9/11 memorial made of salvaged girders from the World Trade Center site. The girders were installed in 2010 as a memorial to the near-3,000 people who lost their lives in the terrorist attacks.

The peace garden also hosts the International Music Camp and the Legion Athletic Camp for youth to attend from around the world.

Visitors to the International Peace Garden need pay a fee for entrance, and citizenship documents are required to leave through the port of entry.

The International Day of Peace is dedicated to the absence of war and violence. Nowhere is that more symbolized than in the simple beauty of thousands of flowers and people collectively enjoying them.

For the rest of this series, please check out the NoDak Moment Archives.