Consider whether or not you would be named a witch

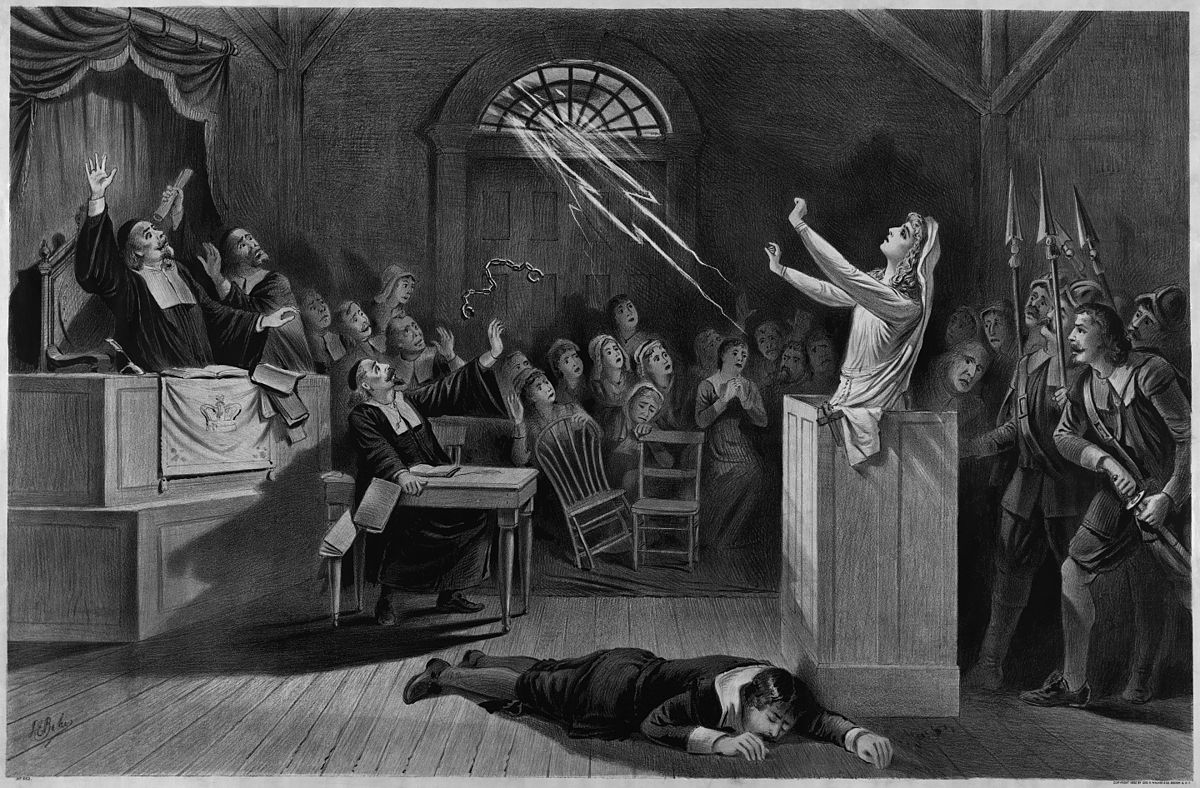

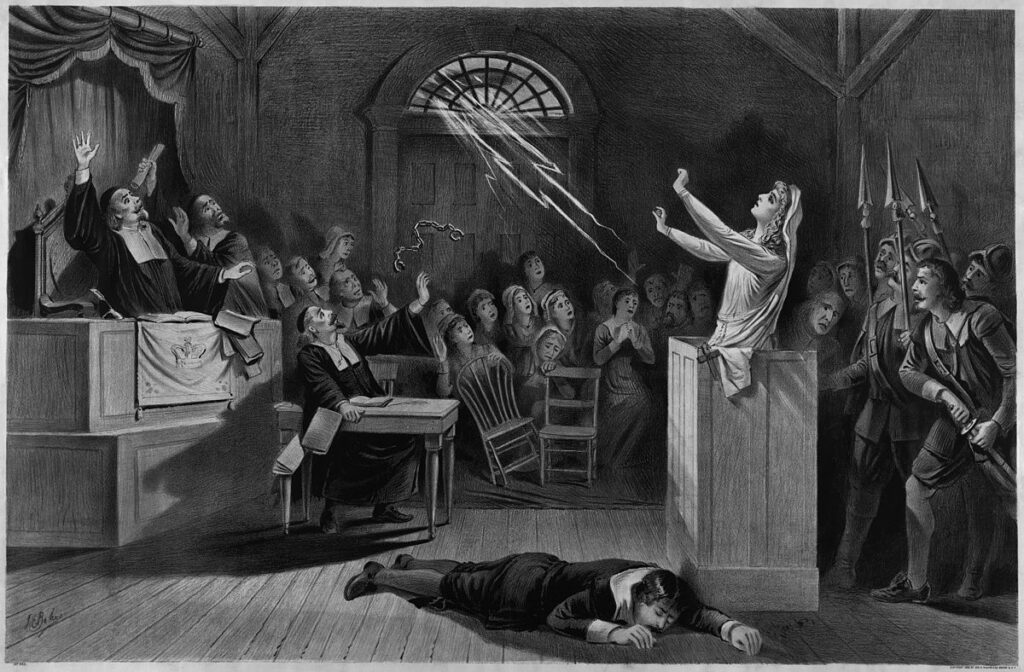

The Salem witch trials have become lore for television shows and young-adult fiction novels. It can be harder to remember that those trials caused mass hysteria that led to the deaths of 19 people and accusations of more than 200.

Between Feb. of 1692 and May of 1963, the colonial town of Mass. was home to the most deadly witch hunt in the history of colonial North America. Looking back, it’s no wonder it’s hard to believe that so many were accused, and more than this, that so many pleaded guilty.

So the question remains: would you have survived the Salem witch trials?

Do you believe in ghosts?

Though believing in the supernatural might seem like a sure-fire way to ‘out’ yourself as a witch, in Puritan Salem the opposite was actually true. It was believed that those who denied the reality of ghosts and spirits were also in denial about the existence of God.

If you denied that ghosts were real, you would be labeled a heretic — a disbeliever of angels. So sorry to all the staunchly anti-ghost, your chances are already looking pretty slim.

Are you a woman?

Here’s the real money question, because 78% of those accused and convicted of witchcraft were women. It’s no accident that when we think of witches today we think of women with pointed hats and black robes. This stereotype has its roots in Puritan belief in the sinful nature of women.

At the time of the trials, the prevailing thought process was that women were intrinsically bad and more likely to suffer damnation than men. Women would have to actively work to thwart the Devil from their lives, lest he overtake their souls.

Not to mention that women were less likely to hold political sway and power. Accusing a woman of witchcraft might land her a stay in jail, where a man might lose his fortune and property, so people were more wary to accuse them.

Are you unmarried or childless?

Women who were unable or unwilling to conform to Puritan standards were more likely to be accused of witchcraft. Something that was pushed heavily by the Puritan church was getting married and having lots of babies. Individuals without a spouse or children were easy targets for accusations.

Although, family was a double-edged sword in Salem society. It was very common for family members of an accused witch to also be accused by association.

“Between Feb. of 1692 and May of 1963, the colonial town of Mass. was home to the most deadly witch hunt in the history of colonial North America.”

Are you wealthy?

Sarah Good, one of the first three people accused in the trials, was called out because of her reputation. Because she was poor, she was thought to be without self-control and discipline, and therefore a witch. Individuals who were known to be destitute were also easy targets because they had little ability to publicly sway others through accusations, which was a common way those accused avoided execution.

Are you white?

Tituba, a famous figure in the trials, was an enslaved woman from the West Indies. She was also one of the three individuals first accused; with her cultural differences being the main evidence for her possible ‘crime’. In general, individuals who were othered, either through their race, culture or lack of freedom, were likely to be accused of witchcraft.

Do you wear ‘odd’ clothing?

So the Puritans were a little fast and loose with the word ‘odd’. Apparently wearing black clothing was reason enough to be considered a witch. Bridget Bishop was accused and later hanged because she wore black and owned a coat that had an awkward cut. You can’t make this stuff up.

Do you have any enemies?

Before the witch trials, Salem was a politically fraught and tense place. Scandals, grabs for power and feuds left huge rifts in the community. With this, it is commonly believed that individuals with personal grudges would accuse their enemies out of spite.

There were many ways to accuse people, and with very little work on the accusers’s part. If someone said they saw an apparition of an individual, a spectral vision trying to afflict them, then that person they saw was affected by the Devil. All someone would need to do is say the spectral vision was of their greatest opponent and that would be considered admissible evidence.

Or, another form of proof was if someone was having a fit; a very common affliction at the time thought to be a symptom of hysteria. If the accused touched the individual and the fit stopped, then they were a witch.

Do you read horoscopes or make your own lotion?

This one might sound really out there, but just about everything was a sign of being a witch. If you owned books on palmistry or horoscopes, owned some sort of mystery ointment or had a birthmark — called a witch’s teat — this could be proof enough that you were practicing witchcraft.

That means every person out here using Co-Star, making do-it-yourself anything or the greater part of the population with birthmarks or moles would be accused with very little fuss of practicing witchcraft.

So would you survive the trials?

Probably not. Anyone with convictions, opinions or the unfortunate habit of being in the wrong place at the wrong time would not have avoided accusation.

What occurred in Salem can seem ridiculous now, but it is a prime example of what can happen when political manipulation and abuses of power lead to religious extremism, false accusations and problems in the justice system. All of these dangers aren’t too far out of our current national reality.

The Salem witch trials aren’t just about remembering a historical event that seems now better-suited for television, they are a reminder of the gendered, racialized and political history of our country. As a woman without children or a husband, who often wears black and checks my horoscope, I wouldn’t have lasted two seconds in 1690s Salem, but that’s for the best.