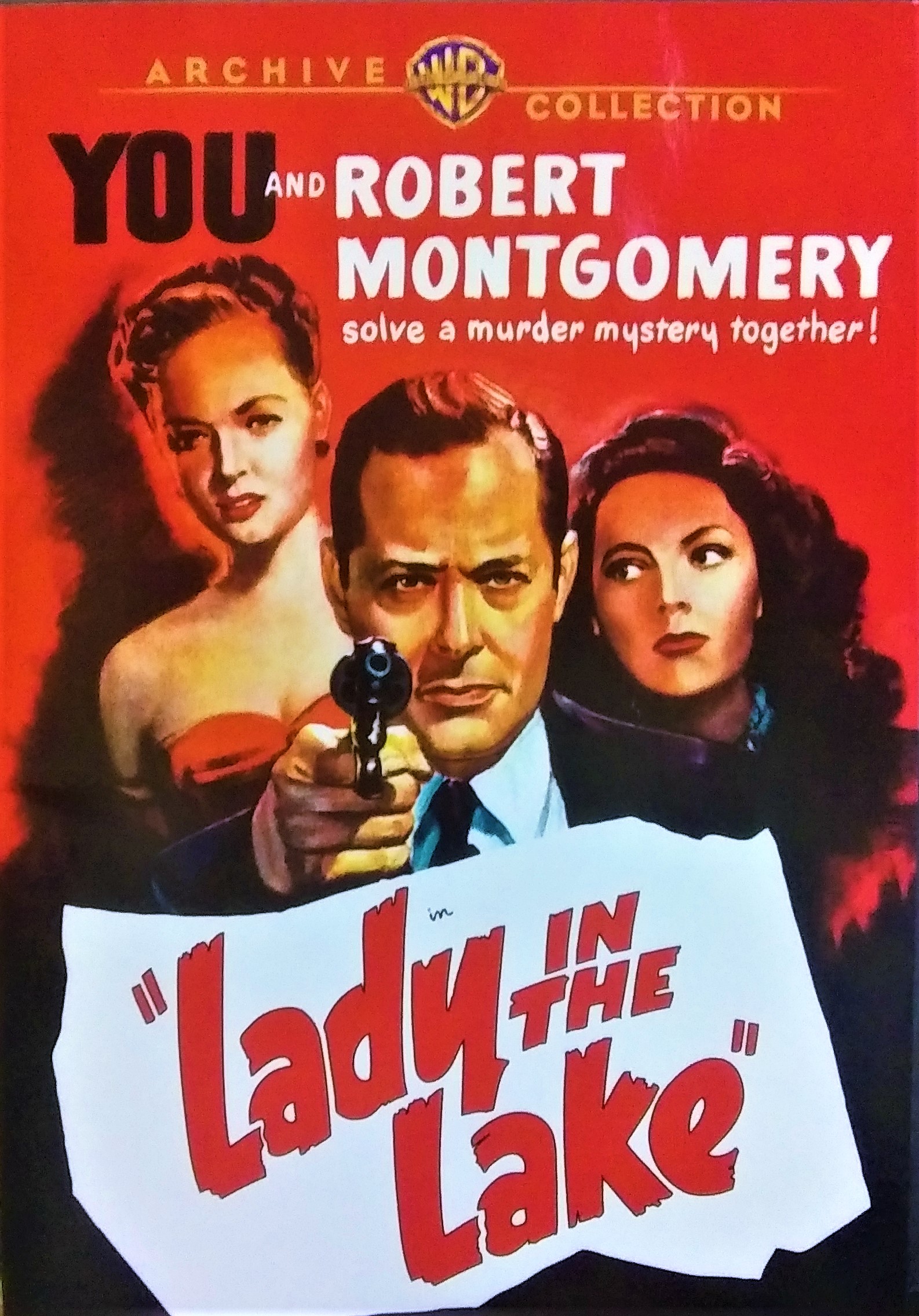

Photo Courtesy | Patrick Ullmer

How does the film stack up to the novel?

In preparing for the upcoming “Death on the Nile”, I decided to cover a property based on another murder mystery helmed by its lead actor, this being another Phillip Marlowe mystery by Raymond Chandler, “The Lady in the Lake.” This would be a rather unremarkable piece of work, had it not been first of the thus far few films to be shot entirely point-of-view.

The book

“After the first murder, the next murder is easy.” This is the more mean-spirited of Marlowe’s cases with brutal murder discoveries paired with Marlowe’s sardonic wit both encapsulating and heightening the experience; “Lavery was at home…and he was very, very dead…Not Lavery’s lucky day.”

In this story, Marlowe is hired by an estranged businessman to find his lost wife, Crystal who had announced her decision to divorce him and marry her boyfriend, Chris Lavery. While investigating Lavery’s lake cabin he discovers a dead, decomposing corpse of a woman who is believed to be a different person. Marlowe has suspicions however and is about to confront Lavery only to find him murdered by his unknown partner-in-crime.

The story is a bit convoluted, but more easy to follow than “The Big Sleep”; that being said, I wasn’t as engaged by this story as I was that one. On that note, this was the book that established the character of Marlowe as one who used his suave personality to get information. A scene in which he innocently trifles with a secretary to gain information is what paved the way for a scene in which he does such with a female book-salesman in the film adaption of “The Big Sleep” in the most PG-rated flirting scene I’ve seen (PG-for smoking, as in the gorgeous librarian played by Dorothy Maguire, no tobacco used.)

As a whole this book is enjoyable. It’s not the best of the Marlowe mysteries (“The Big Sleep”) nor even my favorite (“The High Window”), but it still remains and interesting work, worthy of more attention.

Review 4/5

The film

Released in 1946, the film changes much of the book’s story; such as its summertime setting to a winter one, adding a love interest played by Audrey Hotter- I mean, Audrey Totter who plays a hottie-Totter- I mean a ‘hoity-toity’ secretary who employs Marlowe to find the missing wife of her boss who had gone missing. However, Marlowe (Robert Montgomery) isn’t sold on her ulterior motives and has plans of his own, leading to an immersive experience in point-of-view cinematography.

As a visual experience, this film is perfect. The filmmakers hard work shows in every frame. The POV shots following in-sync with Marlowe’s dialogue, the camera shifting up and down when he stands and sits, Marlowe’s shadows and reflections shown in the walls and mirrors and the cigarette smoke wafting up from the bottom of the screen make this worth seeing for such alone.

The story struggles. This Phillip Marlowe doesn’t feel like his book counterpart who was shrewd and obnoxious at times, but not Montgomery’s level of cranky. This “Marlowe” also jumps to conclusions and bears down upon characters he believes are guilty, another thing his counterpart wouldn’t do.

The finding of Muriel in the lake was such a horrifying and pivotal point in the book (“The body followed…grey-white face, without eyes, without mouth, just long yellow hair. It was not a pretty thing- after a month in the water…”) Here, the scene is just glossed over with narration. It’s like if the authentic “Maltese Falcon” was never actually shown in “The Maltese falcon” (1941)- wait a minute.

The murderers are too easy to see coming; if you run into a woman walking downstairs with an empty gun and a immeasurable sassy attitude, there’s no question she did it. As a whole the experience is great, almost surreal with its execution. Had the film not been in POV, I wouldn’t be covering it and not only was its techniques ahead of its time, but it remains so today in bringing a skilled visual presentation to the screen.

Review 3.5/5

Upstanding results of Montgomery’s filmography both as an actor and director are few and far between, however he eventually directed President Dwight D. Eisenhower for his TV addresses, a bigger feat in politics for an actor than what most actors/directors/celebrities accomplish through activism today.