Having an augmented reality (AR) sandbox on the campus of North Dakota State had been a dream of Jessie Rock’s since about 2014, by her estimation.

Jessie Rock, a geology lecturer at NDSU, teaches a topographical map course. In this course, students typically struggle when they only have access to two-dimensional maps, while they try to perceive the three-dimensional topography, according to Rock.

The students struggled with two-dimensional maps until the five AR sandboxes were introduced in the fall of 2016 when the Student Technology Fee grant was awarded to Rock and her peers to obtain the equipment.

Sara Gibbs Schnucker, an NDSU student studying geology and Spanish, loves the sandbox, and she believes it enhances learning. Citing one of her experiences as a teacher’s aid, teaching with and without the sandbox made a real difference in time and level of understanding. Before the sandbox, she remembers some students struggling to understand topography through a black and white two-dimensional map alone, but she has witnessed that time becomes reduced and has seen students more engaged.

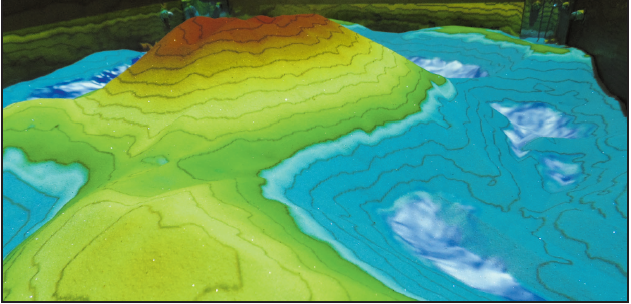

The sandboxes simulate a three-dimensional landscape, using colors and lines to differentiate altitudes. The colors are used to show water, height and even lava. The program for the lava was created by NDSU student Wren Erickson.

When describing how it works, Rock said, “The augmented reality sandbox uses a computer projector and a motion-sensing input device, a Kinect, mounted above a box of sand. The user interacts with the exhibit by shaping special ‘kinetic’ sand in a basin. The Kinect detects the distance to the sand below, and a visualization and elevation model with contour lines and a color map assigned by elevation is cast from an overhead projector onto the surface of the sand. As users move the sand, the Kinect perceives changes in the distance to the sand surface, and the projected colors and contour lines change accordingly.”

Rock said that this accelerates learning, it makes it more enjoyable and fun and it’s available anytime in the basement of Stevens Hall.

“You get to make your world,” Rock said, joking that students can play God with this simulation.

The applications to topographical maps are to help students read them by first letting students build a landscape before color is removed and features are added that would normally be present in a two-dimensional map. Through this, the students pick up more on how to read a map and what the different lines mean.

Through understanding how to read topographical maps, students are better prepared for the world. Rock said that in the event of someone only having a topographical map to read, it’s important that they can do so — it could potentially save their life.

Although the AR sandbox has capabilities to improve learning in the geosciences, it also has applications in architecture, art, engineering and many other disciplines.

Ben Bernard, a computer science specialist that works with the architecture department at NDSU, explained that its applications to landscape architecture are highly valued. Students can play with different landscapes to see how a structure would hold, what kind of flooding it may experience and the overall security of a structure relative to its location.

Rock encourages students to head over to the basement of Stevens Hall to try out the sandbox because their student fees paid for it.