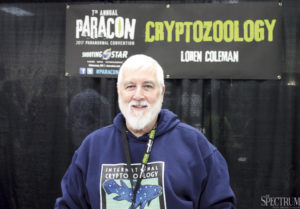

Loren Coleman founded the International Cryptozoology Museum after starting his cryptozoology career in 1960.

Loren Coleman’s career started when he was 12 years old, in 1960.

Since then, the anthropologist, zoologist and psychiatric social worker has contributed to 100 books and 6,000 articles, sharing his research in the field of cryptozoology.

Coleman started the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine and continues to search for cryptids around the nation and world.

At ParaCon 2017, I asked Coleman a few questions on how he got involved in cryptozoology, how it’s boomed since he began his career and what, exactly, is cryptozoology.

Paige Johnson (PJ): How did you get involved in cryptozoology? Is this something you’ve wanted to do for your entire life?

Loren Coleman (LC): Depends on what you define as life.

I started in 1960. I was 12 years old. I saw a movie called “Half Human.” I went to school the next week — ’cause I saw it on Friday — and I asked my teachers, “What is it about the yetis in these mountains of Asia?” And they said, “They don’t exist. Get back to your studies. Leave me alone.”

That stimulated me, out of curiosity, to really start reading about it. I got a book called “Abominable Snowman” the first year into my studies, and I actually went through the book. I got every proper name out of the book, and I started writing those other researchers. I had 400 correspondents in the first year.

I had one teacher, in the next year after that year, who was actually able to get me a flag from the Yeti Expedition of 1960 from Sir Edmund Hillary.

I wrote articles — 6,000 articles. I wrote books — I’ve written 40 books, forwards and introductions to another 60 books. So I’ve been connected to 100 books.

Once you start writing books, the TV people call you. They want you to be a consultant; they want you to be an interviewer. Since I started earlier, I was really a lot older than the Josh Gates-type of people. I was the white-haired old man, who happened to be part Cherokee, who they called to do their interviews. I’m not an actor like him, so I was just an expert.

Then, the whole conference thing started coming up. It started blossoming really in the late ’90s. Last weekend I was in Texas, before that I was in Kentucky. Then California this year.

Cryptozoology is a fascinating field to me. A lot of people write about and are interested in Bigfoot because humans are narcissistic. They really want to talk about something that’s close to them. But I’m interested in black panthers, giant snakes, Mothman.

Because I’ve traveled so much, I’ve gathered souvenirs. Because I really think crypto-tourism is so important. This area, for instance, I’m asking a lot of people, “Where have they seen it? Where do they know about it?”

For instance, in Detroit Lakes, there’s a tradition of the Hairy Man. That could become a site where they could have a statue; they could have an annual festival. In these small communities around the country, these cities like Roswell or Point Pleasant, economies could really be boosted with crypto-tourism.

PJ: Why do you think cryptozoology has boomed? I know you said in the late ’90s, I know that’s when “The X-Files” came out. Why do you think it’s started to grab the people’s attention?

LC: I think there’s two things with cryptozoology: people love animals and people love mysteries.

So, the combination of the two with television, with some movies (like “The Mothman Prophecies,” came out in 2002.) And this was a book that came out in 1975.

What you found at the end of the century, a lot of skeptics came out and said, “There’s a lot of hoaxes,” but there’s also an open-mindedness.

It’s interesting; this is the most open-minded month. October and Halloween brings a lot of people out about ghosts. They’re not afraid to talk about Bigfoot. If you think about that in terms of the years, really from the ’90s through now, there’s been an open-mindedness.

At ParaCon, Coleman invited passersby to indicate where they’d seen cryptids in Minnesota.

If you step back, history’s going to say: this was a time when you could openly talk about this without losing your job, losing your partner and a lot of stuff that used to happen to people.

People are coming by here, and I think this is my fifth time I’ve been to ParaCon. Every time I’ve come, I’ve noticed the native peoples here. Because I’m part native, I’ve dealt a lot with the Cherokee and Mi’kmaq in Maine.

The native peoples here are very open to the Bigfoot conspiracies. Because it’s just part of the landscape here. It’s not something different; it’s not something to be ridiculed. Not something to say, “Well, did that even happen?” That’s very refreshing.

PJ: What’s the difference between myths and legends and cryptozoology?

LC: Legends are always things that have a fire below the smoke. Myths are from human imagination.

There’s a word that I’m very careful about in cryptozoology. Belief, because I don’t believe any of this. Belief is a religious-based, faith-based conceptual way of looking at the world. I accept or deny the evidence based on the facts. We look at legends. We look at facts.

We don’t really concern ourselves with myths. Because, you know, the Minotaur, the harpies, or in some ways even fairies are all myths.

But things like Bigfoot, Wendigo, sea serpents, the Loch Ness Monster, those are the celebrity cryptics, as we call them.

But then there’s little reports of Orang Pendek, a little creature in Sumatra that probably will be discovered.

Our logo is the coelacanth. The coelacanth was discovered in 1938 off of Africa and had been known by the native people that called it gombessa. They actually ate it. It tastes awful. It’s oily; they used a lot of spices. They knew it was there, but none of the scientists did.

They found out that it was actually a fish that had been extinct for 65 million years. So, it’s a living fossil. The word living fossil was first associated with this. Then, miraculously, 30 years later, in 1968, off of Indonesia, 6,000 miles away, they found another species of coelacanth. Not supposed to exist, but there it is.

So, those are the kinds of things that are really important. Not just Bigfoot and Loch Ness Monster.