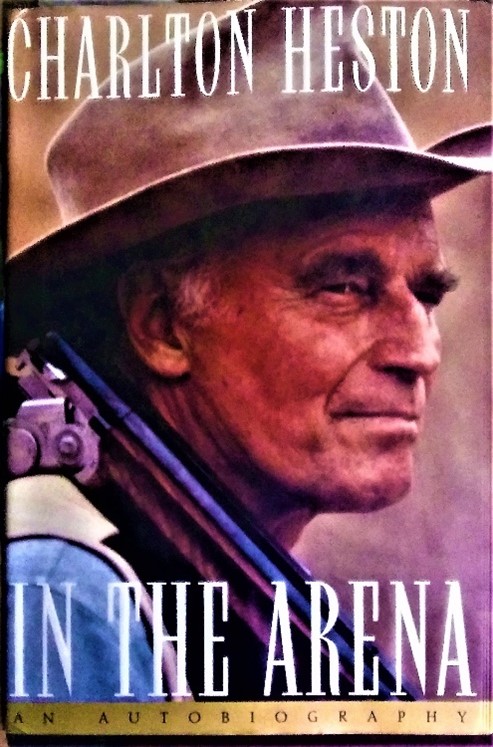

Charleton Heston’s autobiography

I planned to review Sandra Bullock’s “The Lost City,” but upon reading IMBD’s parental warning of a “man’s buttocks shown up close for a prolonged period,” I was seized with an unalterable terror of the prosaic atrocity done to my sight and esteem (which I still think I have) especially considering the last film I saw in theaters was so packed I was forced to sit in section; so I decided to read Charleton Heston’s memoir instead. From “The Ten Commandments” to “Ben-Hur,” and “Soylent Green” to “Planet of the Apes,” Heston left a legacy of epic, biblical proportions. The first chapter is called, “In the Beginning” to which he immediately clarifies, “No, we’re not going back that far. I just mean my beginning…”

According to Heston, he was born in unincorporated suburbs of Chicago called “No Man’s Land.” His parents divorced when he was 10 years old. “I think of my mother as a heroine from a Bronte novel —‘Wuthering Heights’ or ‘Jane Eyre’.” (Writer’s personal note: I associated mine with Jane Eyre.) “My father was a good-looking man of immense charm, with a rich bass voice (the latter was perhaps his most useful bequest to me — it’s gotten me a lot of parts).”

Heston studied acting in Winnetka Theater and Northwestern University where he met his future wife, Lydia Clarke. While he was serving in the second world war, he proposed to her and she accepted via telegram. His choice to pursue a film career was done basically on the fly as he had originally intended to pursue theater. After playing many parts in the low-budget, highly-moody Noir crime films of the time, he worked with Cecil B. DeMille with whom he really clicked and who cast him as Moses in “The Ten Commandments” based upon the likeness he had with Michelangelo’s sculpture of the prophet.

“The Ten Commandments” changed his career forever. Heston was originally shooting “The Private War of sergeant Benson” and was told he wouldn’t be available to shoot “Commandments.” Adamant about playing Moses, Heston agreed to shoot “Sergeant Benson” in a rushed schedule for no salary, receiving a percentage of the gross; “I feel… pleasure every time Universal mails me another check for my share… It’s also a good picture.” Of his performance as Moses, Heston considers it, “Generally impressive, often very good, and sometimes not what it needs to be… I wish I could do it again when I’d need less makeup and could provide a more deeply honed native gift. Never mind. I had my shot at it.”

Epics became Heston’s bread and butter and he would win the Academy Award for best actor in William Wyler’s “Ben-Hur” (1959). According to Heston, he wasn’t the first choice as the studio considered actors “…ranging from interesting (Burt Lancaster) to dead wrong (Rock Hudson) as studios usually do.” It was Wyler who settled on Heston for the lead role, making film history once again. “After I’d played Moses, John the Baptist and Judah Ben-Hur, Willy Wyler said I was the best imitation Jew in Hollywood.”

His coverage of playing John the Baptist in George Stevens’s “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” is fascinating, especially in his explanation that Glen Canyon, Arizona, the location for the Jordan river during the baptism scenes are now all submerged in water, making this film the last time the location was inhabitable. “The U.S. Army Corp of Engineers… agreed to wait for us [to finish filming] before closing the dam and filling several thousand acres of canyon with water, which put the Engineers in the place of God.” Only recently has there been a push to drain Lake Powell from Glen Canyon Dam due to it being no longer needed.

Heston was also an activist and his concern and reverence for the United States is expressed by the end of this book. “We believe in the power of the future, and that we, as a nation can do things better… This country is still what we’ve been from the beginning — an example to the world. Man can live free… we are still to the rest of the world, the shining door to freedom.” So, let it be written, so let it be done.